This article is the next in our series on the future of aging: interviews with people who are experts in their fields and are also visionaries. We’re asking them to talk about what they believe will happen in the years ahead to change the experience of aging.

Carol Marak is a solo-aging advisor and advocate. Since 2016, she’s been educating people about how to age confidently without a spouse or adult children to rely on.

On a warm, sunny day in May 2007, Carol Marak was hiking on a trail in Texas, missing her parents—when she stopped in her tracks, her future flashing before her eyes.

“What am I going to do?” she thought.

She’d just come from her father’s funeral. He had Alzheimer’s. Her mother, who had multiple chronic illnesses, had died four years earlier. Marak and her two sisters had been family caregivers for eight years.

Marak, who was 56 and single with no children, had worked full time throughout in technology sales and blogged about caregiving on the side. By this time, she and her siblings were exhausted.

But if things were that hard with a whole family helping out, what would happen as Marak got older with no family nearby? “I thought, ‘Holy crap!’” she recalls. “‘What am I gonna do? I have no one.’”

“That was my huge, wake-up call. I knew immediately, I have got to prepare for this.”

Within a couple of years, Marak had decided not just to prepare herself but to help other solo agers. She started a Facebook group on the topic. And things snowballed.

The Challenges of Aging Solo

Almost three in 10 people 65 and older live alone today. That’s up 50 percent since 1960. They often describe themselves as “aging alone,” “solo agers” or “elder orphans”—typically meaning they have no kids or siblings, or at least none nearby.

This poses special challenges. With no family members to look out for them, what happens if their cognition starts to decline? Who will take care of finances or help them find care? Similar questions must be asked regarding mobility and other health problems. If they break a hip, for example, instead of having an adult child become a caregiver, they’ll have to hire help.

Solo agers may have to pay alone for housing—and pay for transportation if they can’t drive. They may have no one to check on them during hot summers and cold winters, and they face the prospect of loneliness, especially if they become homebound.

Marak’s Facebook group, which she started in 2016, is called Elder Orphans. It now has more than 9,000 members. Her hiking revelation has led to a career as a solo-aging advisor and advocate, helping people prepare for aging alone. She gives speeches, does webinars and offers group coaching. And she has a book coming out in 2022, Solo and Smart.

Marak advises potential solo agers to start preparing as early as age 45. She was 56 when she started and wishes she’d been younger. “You don’t have to come up with a plan at 45,” she says. “I’m just saying, start thinking ahead.”

Here are the preparation steps she recommends:

- Assess your current, long-term needs (finances, housing, location, transportation, support team, social connections, health, fitness).

- Build support, connection and community.

- Find purpose and live accordingly.

- Write out your plan and follow through.

- Be flexible and open as your life evolves.

We spoke with Marak about her tips for aging alone and what she believes the future holds for the expanding population of solo agers.

SCF: You talk about growing older confidently when solo aging. Is that possible? It seems like there are so many things to consider. Can people prepare for them all?

CM: I think it’s possible. I’ll turn 70 this year, so this has been on my mind for 15 years, and I’m so much more confident now than when I was 55. The key ingredient is self-reliance.

SCF: Single people probably naturally lean toward being self-reliant, right?

CM: You would think so. But I still see people in my Facebook group that don’t feel confident about their capability to take good care of themselves. They still eat junk food; they still go to McDonald’s. They don’t exercise. They sit and watch TV. It’s like, are you kidding me? Well, no wonder you’re worried! No, you’re not going to be confident that way! [Laughs]

Five Questions to Ask about Home

When looking for a home for the older years—or evaluating a current home—Marak recommends asking the following questions:

- Does it make me feel content and satisfied? Or is it a burden on my peace of mind?

- Can I afford it? Can I maintain it? Is it age-friendly?

- Does the location make me car-dependent? For example, in the suburbs and rural areas, shops and clinics aren’t usually within walking distance. What if you can’t drive? What are the transportation options?

- Can my family or friends reach my home quickly, any time of day or night, if there’s an urgent need?

- Does the home and location put me in a position where I’m alone most of the time? Would I be more content with an area that allows easy access to companions and social activities? If moving isn’t an option, how will I stay socially connected to friends and companions?

SCF: What’s the first thing people preparing to be solo agers should focus on?

CM: Well, that’s really up to the person. However, for me it was health. And my health was pretty good. My money was horrible. You would think I’d focus on my money first. But for me, because of my mom’s chronic illnesses and my dad’s Alzheimer’s, I wanted to focus on health because if I didn’t have that, it didn’t matter how much money I had, in my own assessment.

This is all very personal. And that’s something that I teach: nobody can tell you where to start. Only you can.

SCF: When you say it like that, it’s kind of empowering.

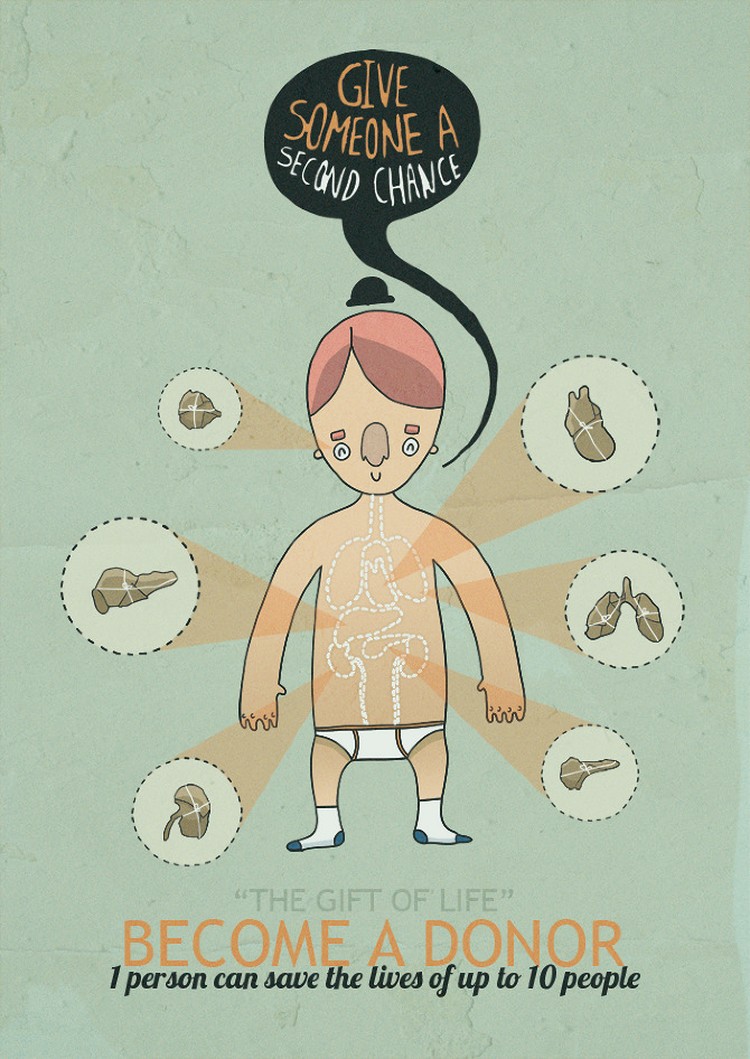

CM: And that’s the key. We want to feel empowered, right? Do you know [senior- living innovator and entrepreneur] Dr. Bill Thomas? He once said to me, “Carol, you don’t ever want strangers taking care of you.” And that stuck with me. I don’t want strangers making decisions for me when I get older. Doesn’t that sound horrible? I’d much rather have a good friend—or a good neighbor, or someone that I’ve built a relationship with, or a sibling—to make those decisions. And that’s why it’s important to maintain that kind of relationship.

SCF: Step three of your “ways to age alone” plan is, “Find purpose and live accordingly.” This is something many people aspire to. Why is it important for solo agers in particular?

CM: It gives them a sense of community. It gives them a feeling that “I’m connected to something,” because if you’re alone and you have no purpose—something to get you out of bed each morning, besides watching TV or eating something [that’s not good]. It keeps you connected.

And people misinterpret purpose. They think, “Oh, I don’t want a purpose. That’s too much trouble.” They think you’re out there to change the world. And that’s not what purpose is. It’s very personal, and it’s inside your heart.

SCF: Can you give an example?

CM: I can give you an example of a teacher I know. She’s 73 now. She’s been retired for about 10 years. She was a fabulous English teacher. She now donates her time at the local library—just a small, rural library. She connects so well with the students. You ought to see some of the projects they work on. It’s just incredible. These kids get so inspired, and they love her.

SCF: That is changing the world in some ways.

CM: Yeah, but it doesn’t have to be big, and you don’t have to make a lot of money at it; it doesn’t have to cost you anything.

SCF: Are there some lesser-known, negative aspects to solo aging?

CM: The negatives to solo aging are the same negatives any senior faces. We all face financial difficulty or questions like, “Will [our] money outlive us?” Hopefully, it will outlive us! That’s a huge concern. “Will our health keep us strong and safe and independent in our home—wherever we live—so we aren’t dependent on the government to take care of us, or a stranger to take care of us, or have to hire a guardian to take care of us?” Oh, those are some horror stories there, you know?

And that’s why it’s so important to start thinking ahead—thinking, what happens if you become cognitively impaired in some way? Who will step up for you and manage your finances?

But we all face it. If you have a spouse, yeah, sure, it makes you feel more comfortable knowing someone’s there, but there’s no guarantee that he or she will be there—or that your kids will step up.

SCF: You mentioned cognitive impairment. Do you advise talking to a friend or loved one in advance about managing your finances, just in case?

CM: Oh, absolutely, yes. And that’s one of the first steps, I think, in starting to make a plan: Get all of your paperwork—legal, finances—organized. And make a budget. Get organized there first, even before you start looking at affordable housing or making social connections, because if you don’t, you’re just going to be worried about all these things that need to be taken care of first.

And your health is very important, depending on how healthy or unhealthy you are.

SCF: Do you have specific advice about saving money or planning financially?

CM: Money is a significant factor when growing older. How comfortable are you with your money, savings and investments? When considering, does it make you nervous, or does the thought of your retirement savings make you calm?

Here are the things I did to set my finances on the right track: hired a financial advisor that I trust. I created better spending habits; before spending, I researched for the lowest prices and avoided spending triggers like going to the grocery market when hungry or buying into the idea that I need this right away—impulse buying. There’s no reason you can’t sleep on it for a few days and find the least costly product or service.

Live on a budget. Yes, you can. I did and still do. If I can do without something for a week, I probably don’t need it. Actively practice gratitude. Find an accountability partner who holds you to your commitment. Don’t shop while you wait.

Think about your earliest money-related memories and experiences. Was money a frequent source of arguments or an avoided topic? What are your current “money scripts” or financial belief patterns? “Money is the root of all evil.” “Money is not that important.” “Money is there to spend.” “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” “I’m just not good with money.” “My family has never been rich.” “Money is a limited resource.” Change your thoughts and scripts about money.

SCF: In general, when aging solo, is there anything that people tend to forget to plan for or that creeps up on them?

CM: The one thing that will creep up on you faster than I can say, “Boo!” is health issues. Don’t ignore your health. Eat nutritious foods, sleep well, stay fit and active, be around loving people who care about you, and love yourself more than you love anything else in the world.

SCF: How do you address people’s fears about aging solo?

CM: If fear is overwhelming, talk with your doctor or a counselor and get help to deal with the fear. I spent seven years in therapy and am glad for it. Otherwise, if fear is ignored, a person will likely stagnate and not move forward.

What helped me address my fears [were] therapy and talking with a trained counselor, then journaling. It helps to put negative thoughts on paper. Spend at least 30 minutes a day, every day, writing out your feelings. It doesn’t matter if the content makes sense or not. What matters is, you write your feelings down as a way of getting them out.

Keep a gratitude list. Pray or meditate. As you put into practice all of these, I promise, the fear begins to dissipate or ease a bit. But you must be consistent. And you must put a plan in place. Learn what’s needed to make your life better. Research and take action steps and look for solutions. Hope is not a strategy.

SCF: You yourself are a solo ager. How’s it going? Have you changed your thinking on any of this as you’ve gone along?

CM: If anything’s changed, I’m probably stronger and more clear and know myself well. I live in a [multigenerational] high-rise so that I’m surrounded by a lot of people that can watch out for me—and me watch out for them. I have made some really good, single friends here, as well as married friends. So it’s nice to be in that kind of environment.

SCF: What are some innovations your parents didn’t have access to that are improving boomers’ experience of solo aging?

CM: There is so much information online! And we have quite a few creative thought leaders in housing, applying different ways that we can age—like cohousing, for example, and creating little support systems where we live, like what they call pocket neighborhoods—and tiny houses.

We have Uber and Lyft. My parents didn’t have access to that. Mother relied on us, the kids, to take her to the doctor.

I also have an app on my phone called Snug Safety, a check-in service. I would have worried a lot less if Mom and Dad had stuff like this. Solo agers can create our own support team with technology and check in on each other.

SCF: Is society headed toward a bright or dim future for solo agers?

CM: I definitely think we’re going in a better direction, only because we’re not hidden anymore. People—senior service providers, the aging sector—are starting to acknowledge us. And the one good thing about COVID-19: it really shed a light on isolation and loneliness. So I think we’re in a good place.

SCF: Is there anything that needs to change to make it even better?

CM: Solo agers really need affordable housing. And it doesn’t have to be an affordable house. It could be an affordable [room rental], but just some ways to create community, so we can take care of each other and be friends with each other as a support team. We need senior housing developers thinking in those lines. Like, married couples—they’ll rent an assisted living or independent living apartment. Why can’t we have a Jack and Jill plan, where you have two separate bedrooms with your own bathrooms? Two solo agers could rent that.

SCF: So far, we’ve talked a lot about challenges. What are the positive aspects of solo aging?

CM: Well, what I love about my life is, I’m alone. I don’t have anyone pulling on me, asking me to give up my privacy, asking me to do something for them, asking me to pay for something for them—like kids will do—and wanting me to put them first. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with us putting ourselves first and taking the best care of ourselves that we can.

So I love my privacy, my alone time. I love me! That might sound weird, but it’s taken a long time to really accept me where I am.

To learn more about Marak and solo aging, visit her website, www.carolmarak.com.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Leigh Ann Hubbard is a professional freelance journalist who specializes in health, aging, the American South and Alaska. Prior to her full-time freelance career, Leigh Ann worked at CNN and served as managing editor for a national health magazine. A proud aunt, Leigh Ann splits her time between Mississippi and Alaska.

Herbes-Sommers, 69, who is now semiretired and studying classical drawing and painting, helps organize large workshops focused around the documentary. We caught up with her for an update on the film—and on the societal changes it proposes.

Herbes-Sommers, 69, who is now semiretired and studying classical drawing and painting, helps organize large workshops focused around the documentary. We caught up with her for an update on the film—and on the societal changes it proposes.

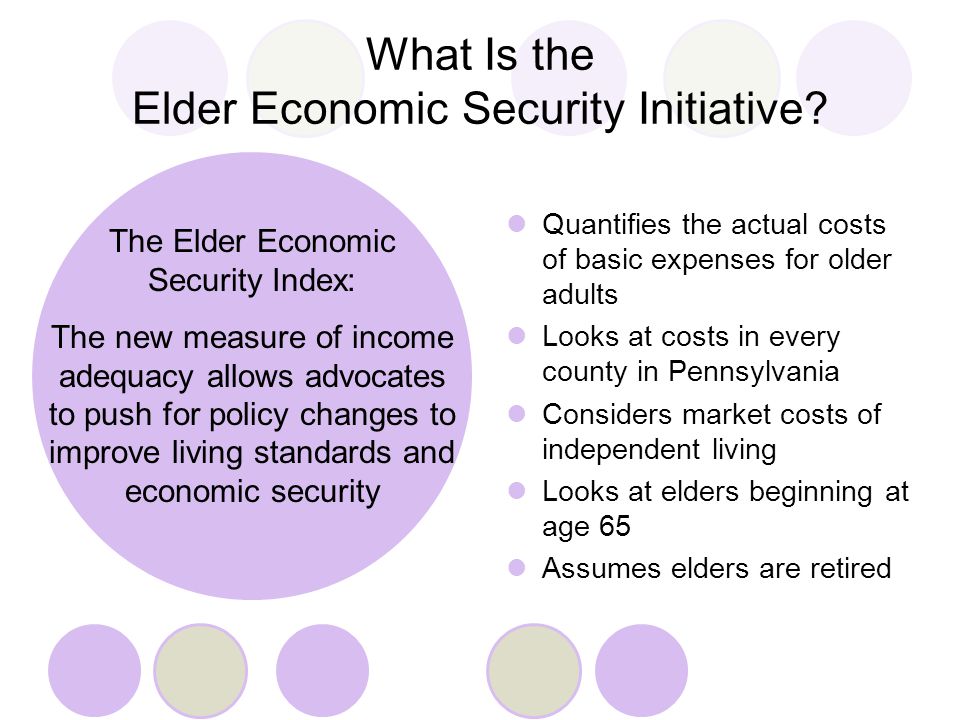

Further, the study revealed specific demographics. People living alone, women, renters and people 75 and older were more likely than their counterparts to live below the Index. Among people living alone, about 84 percent of Latinos, 72 percent of blacks, 56 percent of Asians and 55 percent of whites fell below the Index. And those are just the state averages. The data was further broken down by county.

Further, the study revealed specific demographics. People living alone, women, renters and people 75 and older were more likely than their counterparts to live below the Index. Among people living alone, about 84 percent of Latinos, 72 percent of blacks, 56 percent of Asians and 55 percent of whites fell below the Index. And those are just the state averages. The data was further broken down by county.

Tip 1: If You Have to Quit, Experiment

Tip 1: If You Have to Quit, Experiment Tip 4: Avoid Injury

Tip 4: Avoid Injury