After Jane broke her ankle, walking even short distances was a painful challenge. The 63-year-old had been an avid hiker and gardener and was stifled by her limited mobility. To make matters worse, she couldn’t tolerate the side effects of prescription painkillers.

Then she found relief from an unexpected source: medical marijuana.

“Pot really rescued me,” said Jane, who lives in Brooking, OR, and asked that her last name be withheld for privacy. Fortunately, she lives in one of the more-than-two-dozen states, plus the District of Columbia, where medical marijuana is legally available to treat a wide variety of conditions including Alzheimer’s, Crohn’s disease, arthritis, cancer, asthma, HIV/AIDS, glaucoma, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy and chronic pain, like Jane’s.

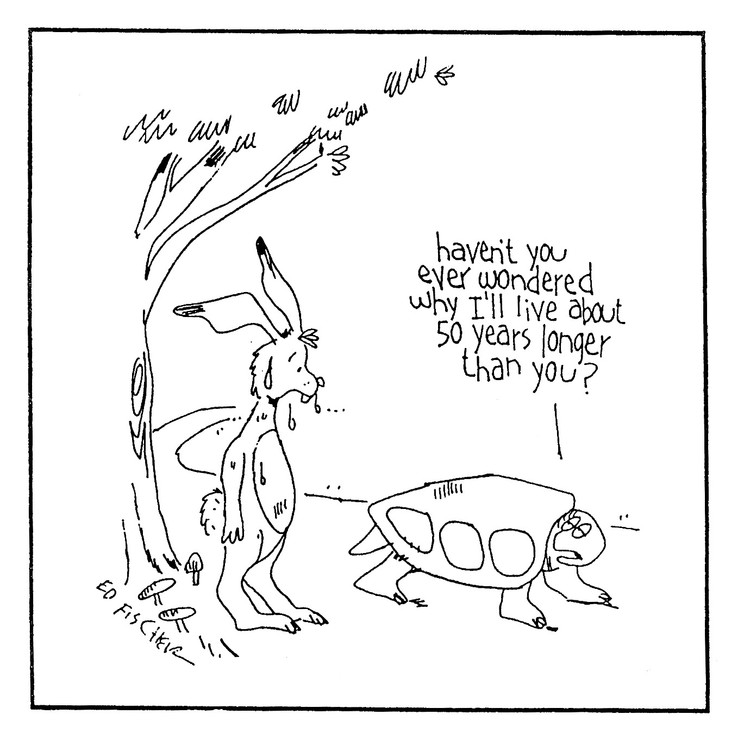

As people live longer than ever before with such debilitating conditions, medical marijuana (cannabis) appears to be welcome as a complementary therapy for some. Over one million Americans now use it, according to Americans for Safe Access. And a recent survey of 31 countries found that about 37 percent of adults who use medical marijuana worldwide were between age 61 and 76.

But a confusing legal environment, a lack of scientific research and unevenness in medical and dispensary training make medical cannabis a complicated choice for both patients and doctors.

Is Pot Really Legal?

Medicinal use of cannabis goes back at least 3,000 years. Its first recorded use was in China in 1500 BC. Many other cultures, including Hebrews, Egyptians, Indians, Greeks and Romans also used it for medical purposes. By the mid-1800s, cannabis was mainstream medicine in Western society too. It was widely used in the United States until 1942, when Congress and the American Medical Association battled over taxing the drug. In 1970, as part of the “war on drugs,” the Nixon administration classified it as a Schedule I narcotic—like heroin. This classifies it as a substance with no known medicinal use and makes it illegal to prescribe or possess it.

Marijuana may help those who have Parkinson’s or dementia

That means, even in states that have legalized medical marijuana, users are still violating federal law. Currently, the Justice Department defers to state assurances that products are tightly regulated and generally avoids prosecuting medical marijuana users who adhere to state guidelines. But people who use cannabis for medical reasons might want to be aware of the risk they’re taking, should the federal government decide to crack down.

Further complicating matters, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved cannabis for medicinal use. The FDA has very specific rules around the types of clinical studies it requires before approving a drug. Although European and Canadian studies demonstrating marijuana’s medical effectiveness for a wide variety of conditions are available, most do not meet FDA standards.

Most US studies, to date, have focused on the harmful effects of marijuana and little data exists on older adults who use the drug for health reasons. Before it will consider approving cannabis extracts for medicinal use, the FDA wants more domestic research, which is tough—but possible—to get approved by the government, said Ken Leonard, PhD, director of the Research Institute on Addiction at SUNY Buffalo.

Both the National Institutes of Health and the American Society of Addiction Medicine have come out against legalizing medicinal cannabis until more studies are completed and approved by the FDA.

Marijuana as Medicine

Legal complications aside, cannabis advocates tout the drug’s use for many aging-related conditions.

“There is evidence that it may help slow progress for those suffering from Parkinson’s disease and dementia,” said Ethan Russo, MD, a board-certified neurologist and psychopharmacology researcher in California. It may also aid common aging complaints like aches and pains and disrupted sleep.

Studies from Europe and Canada have shown that cannabis can be medically effective for pain and spasms from degenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis and for chronic pain from rheumatoid arthritis. Other studies show it may help post-traumatic stress disorder, ease seizures, and control nausea and stimulate appetite in cancer and HIV patients.

Interestingly, although the FDA has not recognized the cannabis plant as medicine, it has approved two medications (dronabinol and nabilone) containing a synthetic form of the cannabinoid THC, which is responsible for the “high” effect, and for stimulating appetite and reducing nausea. Many patients don’t tolerate the synthetics well, but do find relief with the natural plant form, Russo said.

Like all drugs, marijuana has potential risks as well as benefits. There’s a slight risk of addiction, although probably less than with opiates, which are frequently (and legally) prescribed for pain, Leonard said.

“There’s likely to be dosage issues as well, since older people react differently to medications than do younger people,” he added.

Those who take multiple medications should consider marijuana’s side effects, which include rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, slowed digestion and movement of food through the intestines, dizziness and hallucinations.

Getting the Drug

The shortage of hard research on health benefits, coupled with the gray area of legality, means some doctors are still uneasy about recommending cannabis to patients.

Physicians can’t actually prescribe medical marijuana, even in a state where it’s been legalized, because of its status as a Schedule 1 narcotic. Clinicians can only write a recommendation, which permits a patient to obtain a medical marijuana card and purchase cannabis in a dispensary.

New York is the only state that mandates a four-hour, health-department-approved course—costing $250—for clinicians before they are allowed to make recommendations. Other states offer free, voluntary physician resources but do not require doctors to take specialized training before they recommend marijuana to patients.

Neither those dispensing the drug nor the doctors recommending it are necessarily up to speed on what’s best for a patient’s specific needs.

Regulations for growing and use vary too from state to state. Some states tightly control which strains are grown and where, what types of products are permitted and who can legally buy them for a narrow range of medical disorders. Others, such as California and Colorado, are more relaxed; medical cards are easier to obtain and patients are allowed to grow a few plants at home for personal use.

Currently, patients must live in a state where medical cannabis is legal and be under the care of a qualified clinician to purchase it. There’s confusion over whether legal medical users who live in one state can carry and use it in another state where it’s also legal. Some states permit it, but not all. It’s advisable to check specific regulations in your state and in any state you plan to travel to and verify what, if any, use is acceptable.

The conflicting federal and state laws leave some patients—primarily older adults living in long term care facilities—in limbo. Many institutions receive at least some federal funds and are hesitant to flout national laws by allowing residents to use medical cannabis in any form on premises, even if the drug is legal in the state. Some facilities may allow restricted use or forbid staff to handle the drug, said Courtney Allen-Gentry, RN, of the Center for Integrative Nursing and Cannabinoid Science in Omaha, NE.

But this can be unfair to those who find cannabis to be a good alternative to traditional painkillers, Allen-Gentry said.

“You would be surprised at how many seniors in nursing homes or assisted living already use or are open to the idea of using,” she said. Many have successfully reduced their need for other pain medication or antidepressants.

Medicare and Medicaid won’t pay for the drug because of its federal classification. Neither do private insurers. That may change if cannabis’ status changes, but for now patients must pay for it out of their own pockets. The marijuana itself can cost several hundred dollars a month, in addition to a marijuana card registration fee. These costs can be problematic for low- or fixed-income patients, including many older adults.

At the Dispensary

Once a person does get past the many hurdles of the legal and medical systems, the next challenge is figuring out what type of cannabis to actually take.

Licensed dispensaries are the only authorized points of product distribution for medical marijuana. Dispensaries are tightly regulated; several states have “seed to sale” requirements to track each individual plant throughout the growing, manufacturing, transportation, distribution, testing and retail dispensing processes, according to CheatSheet.com. Depending on the state, dispensaries may be under the auspices of the health department, liquor control board or other regulatory agency. Owners and staff must go through extensive background checks, present written operations plans that include patient record keeping, and set up security for both transportation and the dispensary itself.

“Budtenders” staff the dispensaries and guide patients or caregivers in choosing the right product, strain and potency for their specific symptoms. Some budtenders have medical backgrounds; others may pay for private courses that teach them the finer points of medical marijuana’s effects.

Medical marijuana is available in many forms: it can be smoked or vaporized, or it can be made into oils, salves, tinctures, teas and edibles, like candy. Specific state regulations determine what types, such as oils, teas or edibles, and for which conditions they can be sold. The medium can affect how quickly the marijuana takes effect.

Jane said choosing the right product for her ankle was overwhelming. “I didn’t have the knowledge or vocabulary to know what to ask for, but the folks at the dispensary were very helpful.” She chose a tincture, which helps with pain during the day, then added an edible remedy that she uses mostly at night due to its strength.

However, neither those dispensing the drug nor the doctors who are recommending it are necessarily up to speed on what form and strength are best for a patient’s specific needs.

“The industry is poorly regulated at this point, and the average physician has virtually no training,” said Russo, who is a member of the Society of Cannabis Clinicians. Patients are left to rely on dispensary budtenders’ or friends’ advice.

Anyone who is considering using medical cannabis should proceed slowly, cautioned Allen-Gentry. The concentration of active ingredients, called cannabinoids, can vary widely depending on the strain, form and how it’s grown. For older adults, who metabolize substances differently than younger people, it takes time to build up a tolerance to any side effects of cannabis, she said.

Marian Their, 76, of Boulder, CO, applies a cannabis-based salve for chronic pain from a shoulder injury. Cortisone shots didn’t help and she didn’t like the side effects of prescription painkillers. “Not only is it better but it’s kinder on you,” she said.

To Use or Not to Use

A recent Pew survey found a slight majority of Americans (53 percent) support legalizing marijuana. Baby boomers were about evenly split, with 50 percent in favor, 47 percent opposed and the remainder undecided. In comparison, 68 percent of millennials and 29 percent of adults age 70 to 87 support legalization.

Jane was perfectly comfortable with the idea of using marijuana for medical purposes when other measures failed to bring her pain relief.

“Most of us [boomers] smoked pot in college, so when medical marijuana came up, it wasn’t a shock,” she said.

Doctors seem open minded about cannabis too. A 2014 national survey of physicians found that 67 percent support having medical marijuana as an option for their patients and 56 percent think it should be legalized nationwide. In Florida, which has a medical marijuana measure on the ballot in 2016, nearly 90 percent of the population supports the idea.

Shelly Lindeman, 72, of Aventura, FL, is in favor. “What’s the difference between that and getting a prescription for something? I’m not using it to go to a party and enjoy myself, I’m using it to help with a disease. Absolutely I’d use it.”

Shelly’s sister, Elaine Boyarsky, 76, is less certain. “I’ve never needed anything to make me feel OK. For medicinal purposes, yes. But I’m thinking that people might abuse it.”

Advocacy groups like the Marijuana Policy Project and NORML hope to get medical marijuana initiatives on more state ballots and to broaden laws already on the books. For now, with the patchwork of state laws, mixed messages from the federal government, and insufficient information about the safety and effectiveness of medical marijuana in older adults, it’s not surprising that people might find it hard to make up their minds about using cannabis. But it’s certainly something that everyone, of all ages, is taking seriously.

For Marion Their, her decision to use medical marijuana was less about age than it is about shifting priorities.

“As we age, I think we become a little less cautious about what people think,” she said. “Back then, I smoked because it was cool and forbidden. Now, it’s a matter of getting relief.”

Freelance journalist Liz Seegert has been writing about health for nearly 30 years. Her work has appeared in Consumer Reports and Kaiser Health News, on the AARP and New America Media websites and on WBAI-FM/Pacifica Radio. She covers aging for the Association of Health Care Journalists. A native of Queens, NY, she loves to walk with her rescue dog, Duke. You can follow Liz on Twitter: @lseegert.