Treating patients slowed by Parkinson’s, geriatrician Louise Aronson, MD, sings a chorus of “Happy Birthday” in her head to make sure they have enough time to respond. I’d love a doctor this humane as I head into old age, not to mention this expert. But she lives across the country and I’ll bet there’s quite a waiting list, so I’ll have to settle for her as an ally—and what an important ally she is.

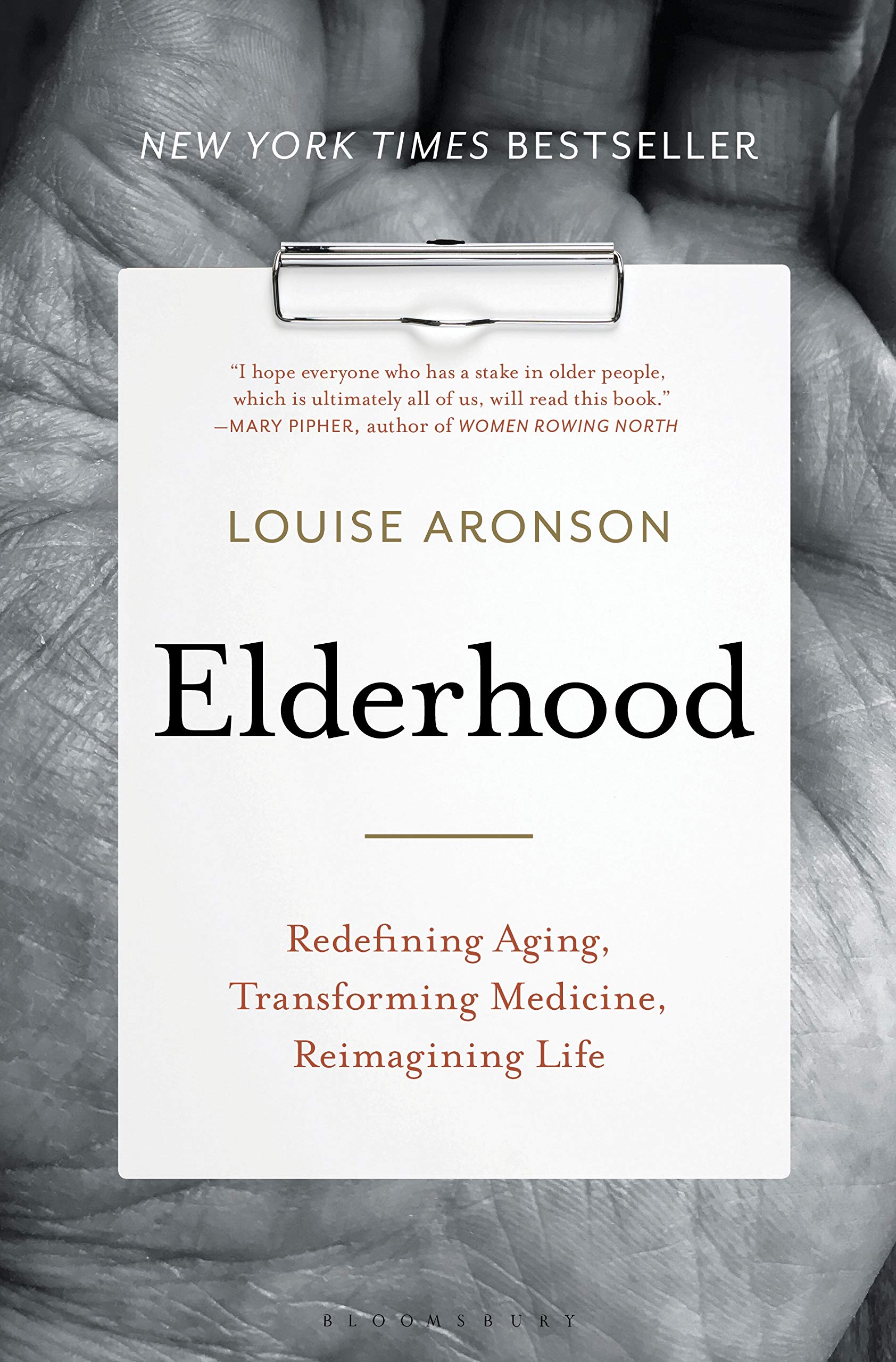

Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life (2019), Aronson’s urgent, eloquent new book, catapults her to the front line of those calling for culture change around aging in general and health care in particular. It’s an expertly argued takedown of a system that:

- makes it far easier for people to see doctors than get the social services that would improve their lives;

- punishes doctors, instead of rewarding them, for tackling the complex needs of older people in a humane, holistic fashion. Many burn out, including Aronson herself, a painful process she chronicles in the book;

- prioritizes the high tech over the human, those in midlife over the young and the old, and curing over caring;

- typically treats the chronic conditions that accumulate over time without taking quality of life into consideration, making more years of debility more likely;

- makes a good death harder to achieve by forcing many people to go on longer than they would like.

The list goes on.

Innovations are underway, but most medical schools have yet to question the profession’s entrenched bias and assumptions. Olders are either undertreated (deprived of treatment that would probably help them) or overtreated (with drugs and regimens that don’t take age into account). Both approaches, Aronson bluntly observes, “are forms of ageism.” So is the omission of older people from clinical trials, which Aronson calls “ridiculous,” likening age limits in osteoporosis studies to “studying menopause in thirty-year-old women.” So is the lack of interest in why men live less long. Again, the list goes on.

Why don’t clinicians spend more time studying the people and complex conditions that require the most medical attention—and health care dollars? Because, Aronson explains, “social forces and cultural rationales determine what doctors study and value.” Left behind are not only the nonyoung but the nonmale, nonwhite, and non-“able-bodied,” and, as she comments tartly, “When people are defined by what they are not, we are in trouble.” Medical advances have very different consequences in a world of much longer lives, yet most institutions ignore those consequences. The result is vast waste and immense suffering.

What we need, Aronson argues, isn’t better medical science and technology, but a profound shift in the underlying culture around age and aging.

Biology matters, but it’s only one part of a far more complex equation that includes attitude, behaviors, relationships, and culture. That’s a terrifying thought in a culture where ageism is more common than sexism or racism, and most people of all ages see old age through a window rendered dark and dirty by negative stereotypes. But there’s hope—beliefs have frequently changed through history, and for individuals, they can change at any age. And when beliefs about elderhood change, the culture and experience of old age, in life and in medicine, will change too.

For Aronson’s blueprint for the necessary, innovative, structural changes to our health care system, read her book. (Read it also for the moving portraits and splendid prose; Aronson is also a gifted writer.) For the necessary shift in our attitudes and beliefs about aging, read mine—This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism (2019). And look in the mirror.

The culture change that both of us demand requires a grassroots social movement, like the women’s movement, to raise awareness of ageism and make it as unacceptable as any other form of prejudice. That change begins in each of us, as we confront our own internalized age bias, begin to unlearn it—and take that shift out into the world. For starters, if your doctor or your parents’ doctor says, “What do you expect at your age?” call him (or her) on it—and find a new doctor.