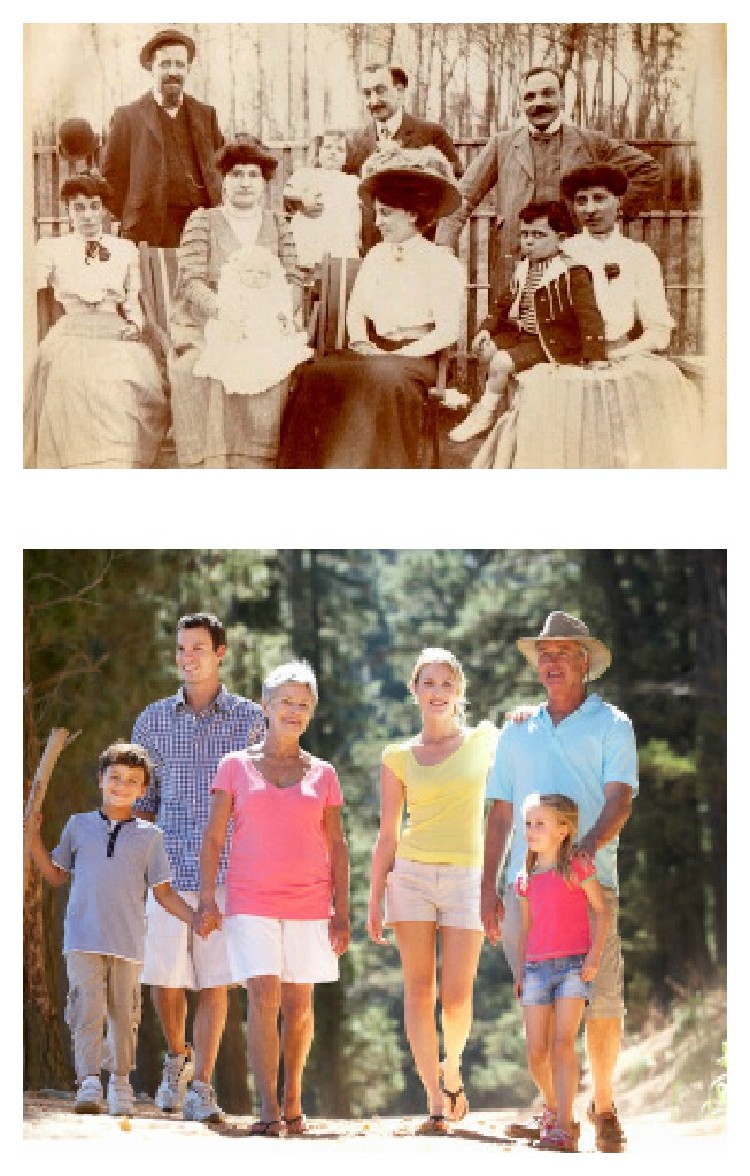

Nestled within the American psyche is a nostalgic image of a three-generation household: an older couple sitting by the fire with grandchildren playing about their feet while the children’s parents look on fondly. Yet in the 21st century, so few families include live-in grandparents that some social critics have accused Americans of abandoning the older generation. Surely, they scold, grown children usually took in their aging parents in the past.

But is that memory rooted in fact? It’s true that there have always been households that included three generations, but according to historians that was never most families, except during the Victorian era. So where did older Americans live in the past? And can that teach us anything about the future?

Colonial Days: Nuclear Families

From colonial times until the 19th century, the vast majority of American homes harbored only parents and their children—nuclear families. That was partly because life expectancy was only about 50, and grandparents were relatively scarce.

Fifty was an average, however, and some did survive into their 60s, especially the well-to-do. But older people rarely moved in with their married children unless they were forced to because of poor health or poverty, or because their spouses had died. Instead, it was customary for at least one unmarried child to remain at home with the parents to ease their workload and to care for them if necessary. That individual generally inherited the homestead or a larger share of the estate.

Some historians believe Americans have always preferred nuclear households, as did people in England and northern Europe, where many early settlers came from. But in their book Old Age and the Search for Security (1994), Carole Haber and Brian Gratton stress that even when the younger generation had their own homes, they didn’t abandon their parents. Usually they lived close enough for parents and adult children to support one another in any way they could.

Why would the older and younger generations of years ago want separate households? Historian Pat Thane suggests that both wanted to be free to live their own lives, a wish that had to be balanced against duty to family—a conflict in values still with us today.

In colonial times, older individuals who had never married and childless widows and widowers almost never lived alone. Widows who owned their homes often turned them into boarding houses, or they became boarders themselves. The community sometimes stepped in to help people with fewer resources, arranging for them to live with relatives or neighbors.

The Victorian Era: Three-Generation Households

In the United States during the 19th century, extended-family households became more common. Victorian society believed in the importance of family—social commentators sometimes asserted it was the basis for the entire social order. Lifespans were lengthening, and couples also married earlier and had children sooner, so families were likelier to have three living generations.

In addition, industrialization was putting more money into the pockets of the white middle class, enough that they could afford to house non-earning relatives, according to Haber and Gratton, but not enough to maintain separate homes. Victorians had large families, so there was only a slim chance that any particular individual would have to house aging parents. In fact, with a number of adult children to choose from, some older people could decide for themselves where they wanted to live. Others travelled between the homes of their offspring without staying long at one place for fear of wearing out their welcome.

Prosperous, white Victorians weren’t the only ones living in multigenerational households. After emancipation, African American families often gathered many relatives under one roof. Some may have been reacting to the deprivations of slavery, which routinely broke up families, but there were also practical reasons. Ninety percent of African Americans lived in the South, and many were sharecroppers who farmed someone else’s land. The older generation needed help working the land and frequently took in nephews, nieces, grandchildren and others.

Meanwhile, waves of immigrants were landing in the United States from parts of the world where it was the norm for parents to live with their married children. They established multigenerational households too.

When older people who lacked family and money were no longer able to care for themselves, they were usually relegated to poorhouses, where they lived among criminals and the insane.

The 20th Century: Independent Living

The 20th century transformed aging and the American family more than once, and in unexpected ways.

At first, three-generation families were relatively common. In 1900, 57 percent of Americans 65 and older—and 71 percent of widows—lived with one of their grown children. It wasn’t always a happy arrangement.

“Harmony is gone. Rest has vanished,” a woman complained anonymously in Harper’s magazine in 1931. Her mother had moved in with her, disturbing her routine and her children and threatening the stability of her marriage. Many of her friends were in similar straits because they lived with an aging parent, she said, yet she felt it was her duty to take in her widowed mother.

It’s possible her mother also felt unhappy if she was anything like another woman, age 73, who wrote anonymously to the Saturday Evening Post a few years later. She was bitter, she said, when “declining health and declining finances left me no alternative but to live with my daughter.” Determined not to be a burden, she made rules for herself: “I must not be around when she was getting her work done, or when she had her friends in. I must ask no questions and give no unasked advice. I resolved to spend the greater part of each day alone in my room.”

During the Great Depression, parents and their adult children often moved in together to save money. Other families broke up because the younger members had to leave town to find work. Before going, those who were most desperate sometimes placed their children in an orphanage and their frail parents in a poorhouse to make sure they had roofs over their heads.

The 1940s brought the first Social Security benefits. Though the payments initially were skimpy, almost immediately living arrangements began to change: soon all but the poorest elders could afford to live on their own. When economists Kathleen McGarry and Robert F. Schoeni analyzed where older widows resided over the course of more than a century, they found that, beginning in 1940, more and more were able maintain their own households. By 1990, just 20 percent lived with an adult child, down from 71 percent at the turn of the century.

Company pensions also fueled that change. For the first time in history in the late 1940s and ’50s, retirement became possible for many as corporations—pressured by unions and rewarded with tax breaks—more frequently offered pensions.

Throughout the 20th century, lifespans kept increasing. In 1900, the average American died at about 47. By 2000, life expectancy had soared to just under 77. Most older people were active and healthy.

Some elders, however, developed chronic health problems, and those without family or funds were in a difficult situation. Poorhouses were driven out of business during the 1950s, thanks to their terrible reputation. With nowhere else to go, many older people, no longer able to live independently, took up beds in hospitals, which weren’t happy about the situation. In 1954 they persuaded the government to help fund separate, custodial facilities to house patients unlikely to recover their health.

As Atul Gawande explains in Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End (2014), these facilities “were never created to help people facing dependency in old age. They were created to clear out hospital beds—which is why they were called ‘nursing’ homes.”

The 21st Century and the Future

As boomers enter their later years today, they’re generally healthier and better educated than previous generations. When asked, most insist they want to age in their own homes. Many will probably do so alone. A third of them are single—divorced, widowed or never married—though most are likely to have family nearby. (The majority of adult Americans live within 25 miles of their mothers.)

Meanwhile, family life is changing. More adults are living together under one roof, but that doesn’t include grandparents. Roughly 20 percent of Americans in their 20s and early 30s have moved back in with their parents or never left home in the first place. Many of these younger people are unemployed or stuck in low-paying jobs with student loans to pay off. Initially, experts blamed their delayed independence on the 2008 recession, but some now suggest this lifestyle may persist for the foreseeable future. If so, many families won’t have the room or financial resources to take in grandparents who can no longer live alone.

Meanwhile, family life is changing. More adults are living together under one roof, but that doesn’t include grandparents. Roughly 20 percent of Americans in their 20s and early 30s have moved back in with their parents or never left home in the first place. Many of these younger people are unemployed or stuck in low-paying jobs with student loans to pay off. Initially, experts blamed their delayed independence on the 2008 recession, but some now suggest this lifestyle may persist for the foreseeable future. If so, many families won’t have the room or financial resources to take in grandparents who can no longer live alone.

What will happen to these older people? They’re less likely than earlier generations to end up in nursing homes. Medicaid, the federal-state program that pays for medical care for those who can’t afford it, has begun to divert some payments from skilled nursing facilities to less costly care at home and in the community. That’s a relief to elders who live alone and for adult children struggling to care for ailing parents, sometimes from a distance. So far, families have provided most of the care older people need and have done it at their own expense, but now home health aides are increasingly in demand, and the agencies that supply them are thriving. There are serious problems with this solution, however, such as high turnover among the low-paid aides.

Meanwhile, the world’s scientists are working on technology to keep people who are disabled safe when they’re home alone. Among other things, they’ve come up with ways to remotely monitor everything from blood pressure to whether individuals take their medications. The Chinese are developing companionable robots that can recognize faces and tell jokes. Some critics are beginning to object, however, that older people need more human contact, not less. Whatever happens, long term care will continue to be a major challenge in the future.

Will it ever become common again for three generations to live under the same roof? History suggests that depends largely on the economy. At least in the United States, it’s a sign of prosperity when adult children and their parents live separately, and a sign of hard times when many move in together—as they did when the recession hit in 2008.

On the bright side, we now live long enough that children frequently grow up knowing not only their grandparents but their great grandparents. A demographer at the University of California, Berkeley, has predicted that by 2030, three out of four eight-year-olds will have a living great-grandparent.

And that’s a situation completely new in human history.

Flora Davis has written scores of magazine articles and is the author of five nonfiction books, including the award-winning Moving the Mountain: The Women’s Movement in America Since 1960 (1991, 1999). She currently lives in a retirement community and continues to work as a writer.