I try to see current movies featuring old actors whenever the actors are famous for their art, or the writing and direction promise to offer us real news about later life. Sometimes—often—I am disappointed. Producers choose sentimental, implausible or burlesque scripts; old actors accept the roles because there are so few available. But since 2006, stellar cinematic culture is suddenly waking us to the deep, universal themes of illness in the context of lifelong marriages. I am thinking of four absorbing films.

Away From Her (2006) stars Julie Christie, regal at 70, as a wife with Alzheimer’s who falls in love with another man in her nursing home. Unfinished Song (2011) provides Vanessa Redgrave in her late 70s with an unmannered role as a chipper, loving wife, dying of cancer, and casts the austerely beautiful Terence Stamp as her dour helpmate. Amour (2012) features Emmanuelle Riva as the 80-year-old wife who suffers two strokes and Jean-Louis Trintignant as the too-long-suffering husband who eventually smothers her. And Still Mine (2013) offers the charming Genevieve Bujold as a wife slowly losing memories but not yet much selfhood or rationality.

Of these four, in my opinion, Still Mine is the movie that lovers and caregivers have equally been waiting for. It offers the most imaginatively productive balance between challenges and resiliencies, between sad realities and butt-headed optimism. Before Irene Morrison (played by Genevieve Bujold) falls and breaks a hip, her husband, Craig (James Cromwell), has already acknowledged that they cannot stay in their two-story house. His desire for them to age in place together drives the plot: his designing and building a smaller house for the two of them, on one floor, with a better view. He has ample skills and strength to construct this himself, starting with cutting down his own old-growth, hardwood timber and sawing his own lumber.

This part is based on a true story about an 85-year-old man in New Brunswick (Canada) who did just that. It wasn’t only that the Morrisons were unwilling to abandon their land; Craig would do anything not to lose Irene to the care of strangers. His boulder-like determination, against the rigidity of the town’s building inspector and their altered health circumstances, is as heroic an aspect of his character as his motive—to care for Irene himself because he knows better than anyone else how to do it. Loving faithfulness can survive even the terror of forgetfulness.

This Best Picture in the Canada Screen Awards of 2013 constitutes the true love story that many viewers desperately wanted Michael Haneke’s Amour to be. Indeed, Still Mine is an antidote to Amour. Unlike Still Mine, there is no sex in Amour. But neither is there much conversation. Early on, Anne and Georges appear in a long shot, conversing with some animation while returning from a concert. But we don’t hear what they say. We never do hear them having a normal, marital conversation, which is the foundation of any good, long-term marriage. After Anne’s strokes, Amour is all emergency speech between them. And remote shocked eyes: Trintignant’s fixed look of stoic readiness for further horror. And he inflicts horrors—on her and on himself.

Still Mine is another genre, of course, a kind of heroic romance–partly because it ends before Irene’s state worsens, partly because Craig’s character determines the resilient tone. Stubborn, unfearful. His steadiness, flexibility and attentiveness, firmed by that long marriage and 85 years of other life experience, reassure us as they do his wife. The dialogue, the heart of this marriage, continues despite the fact that she is becoming cognitively impaired.

Still Mine doesn’t name her condition—no doctor speaks. Instead, it relieves us of the medical model. It doesn’t linger on instances that demonstrate her decline. Only once is Craig flummoxed by her strangeness, when Irene seems to collapse on the frigid lawn and wants to sleep there. Craig is the most patient of husbands but he can’t let that occur, especially if she has just had a mini-stroke. He decides to haul her inside bodily. It is the one time he overrides her autonomy in the entire, two-year period the film covers. He apologizes later.

Unlike the solitary couple in Michael Haneke’s Amour, Irene and Craig maintain a life despite her cognitive impairment. They see friends, have concerned children; a neighbor brings covered dishes. After a lifetime of independence, Craig will accept paid aides to help him help her. It never crossed the mind of Michael McGowan, the man who brilliantly wrote and directed this magnanimous film, that this man would consider his wife a burden and be driven to end her life.

Irene admits fearing that she might forget “everything,” by which she means Craig. But he promises her that it won’t matter. The best answer I know of at such a moment is, “But I will remember you.” There are at least two handles by which to pick up a bad situation, which cognitive impairment can sometimes create. And the desperate one–shown in Amour—however plausibly motivated by frustrated love, pity and fatigue, may destroy everyone.

All four of the films I listed (these two, Unfinished Song, and Away from Her) concern long-enduring relationships that face strain. As such, they are fascinating landmarks for other filmmakers and critics and repay being thought of together. But I have a complaint as a film addict and age critic about something odd that the four have in common. The victim is always the woman, never the man. This is peculiar for films that claim any degree of realism. Men sicken and die earlier than women. Typically, it is women who serve as caregivers. These are male fantasies of health and immunity.

So a plea to authors and directors: when will you make the howl of grief from behind a closed door come from a widow rather than from Terence Stamp (Unfinished Song) as a widower? When will we see a bereft woman reach out a hand in bed (as Craig Morrison does when Irene is away in rehab) toward the empty space her husband had warmly filled? When will you give us a film in which the wife is the patient, or even the not-so-patient, caregiver? When will an old woman perform epic feats to keep at her side the old man she has lovingly aged with?

© 2013 Margaret Morganroth Gullette

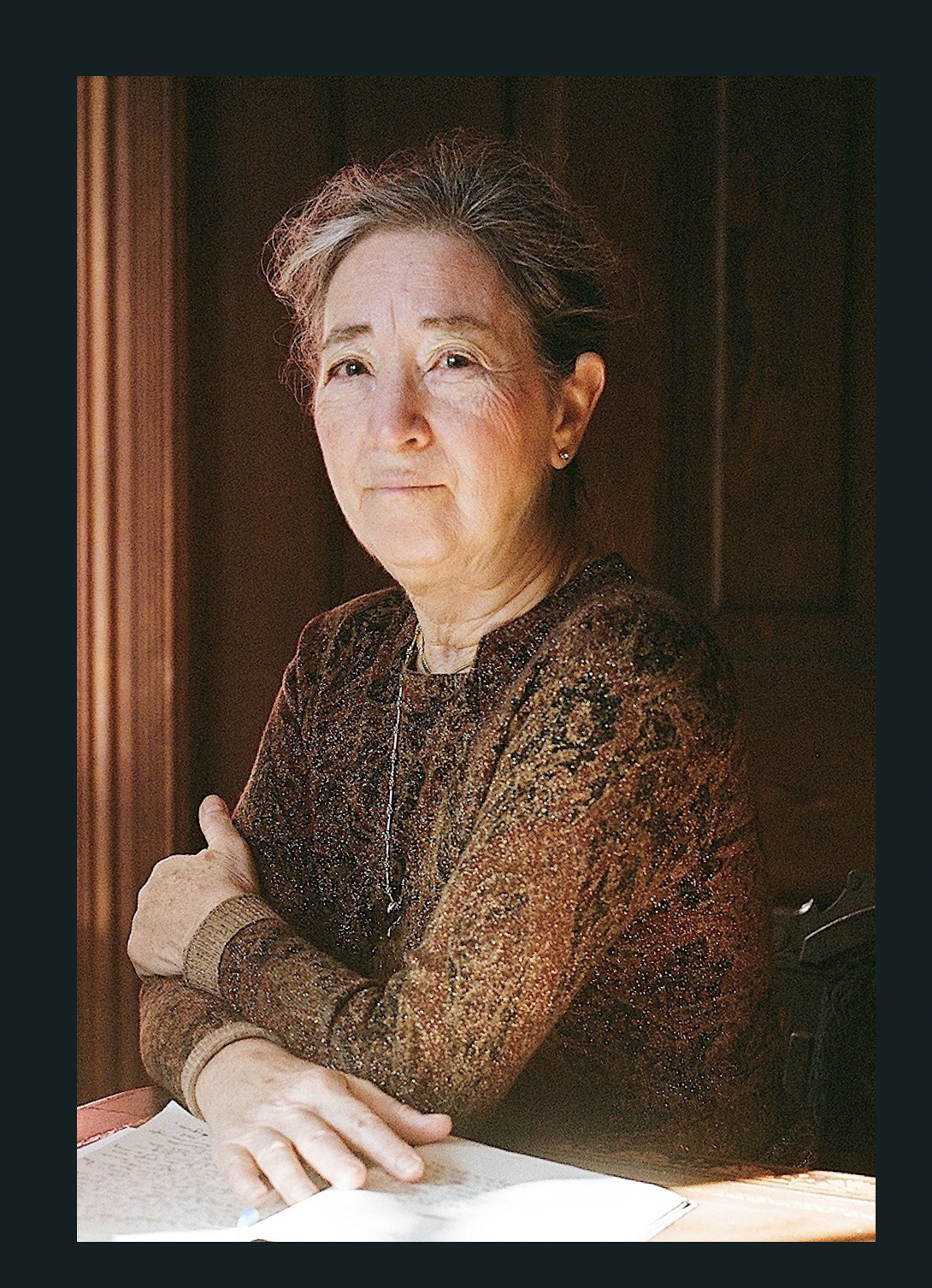

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.