The sex scene in the film Still Mine (2013) made me want to get in the sack with my husband. We haven’t been married as long as the fictional couple in question, who have racked up over 60 years together. They are awfully attractive— Genevieve Bujold as the petite, witty wife, Irene Morrison; James Cromwell as her husband Craig, 6 foot 7 of upright, craggy manhood.

It’s nighttime, and she is already in her delicate white nightgown.

“Let me see your body, old man,” she orders unexpectedly, straight-faced.

If I had ever used such an odd come-on to my husband, it would have had to be more jocular. But Craig is old; he is supposed to be 85. Bujold looks younger than 85 with her lined and glowing skin, tilted smile and that mane of white hair. To her, he is both–old and desirable.

Morrison drops his trousers with dispatch; Irene pulls up her nightgown, revealing lovely breasts. The camera shows them naked to just below the waist, and I dare anyone to say it is not a pretty sight. He has a long, thick torso; Michelangelo liked to draw and paint those complexly muscled male bodies.

They cling to each other. We see his charmed, beaky face.

He has a second of hesitation. But the movie soon cuts to them lying in bed close together, wearing only the lineaments of gratified desire, in the words of the poet William Blake. Younger couples than we might also find themselves turned on.

“We have always been good in the passion department,” she says. And on another occasion when he observes, “You were so prim and proper,” she retorts, “Until I met you.”

But it’s not as if the movie is all about sex. This is only one scene—that I now wish were longer. Every second in such a scene gouges a longed-for hole in the mountain of ageist slag and ignorance that still pollutes our vision of older people. Older people are told to be ashamed of their bodies; younger people are told sexuality dies sometime after youth; some scholars point out that our culture considers “elderly sex” shameful and unwatchable. Meanwhile, in private (it appears) something else is going on. Here, we are privileged to watch it.

The basis of this marriage must also have been conversation. They flirt through speech. They talk all the time—he more amiably to her than to anyone else, including their children. Craig, an articulate version of the stereotypical laconic farmer, can be tetchy with others who don’t match the standards of repartee and sly good sense that Irene sets. He counts on her for these qualities even though he knows she is becoming cognitively impaired.

When she falls down the stairs and he visits her in the hospital, he is the one who says glumly, “I think we’re on the downward slope.”

And she is the one who reassures, objecting vigorously, “I don’t think so.”

“Oh, really? How do you figure that?” he inquires, his head cocked toward her, waiting.

“By all rights, I should have broken my hip,” she says gleefully, looking him in the eye, enjoying winning the point against him and holding their luck solid. She hadn’t broken anything at all.

Unlike other people who think “Alzheimer’s!” and stop treating the person as normal, Craig waits for her responses in the same way, expectantly, that he always did. And, like other people similarly treated, she mainly rewards good expectation. Much remains as memories recede. Many of her recollections are firmly fixed, like her accurate recall of a woman Craig liked too much 30 years before. Her bridge game is still good enough to infuriate the opposing husband in their foursome.

James Cromwell was in fact not 85 but only 72 when the film was made, and Genevieve Bujold was 71. They could plausibly have been married 50 years, but not 60 plus. I wish the film had given the actors’ actual ages, not the ages of the real people the film is based on, so that, while viewing the sex scene, younger people could reflect admiringly, “Wow. So this is what 70 looks like. I can live with that.”

More than ever, we need the companionship of such stories on the long road where romance that has survived everything else runs head on into severe disability.

Still Mine manages another surprise in its gender politics. Where many “damaged” wives are repudiated (I think of Newt Gingrich and John Edwards, two American politicians who abandoned wives with cancer), Craig is righteously possessive about his long-beloved partner.

The last atypical accomplishment of this superb film, if I may speak personally, is that I identified with both people, enthralled both ways. I could be the one offering patience-centered care, who delights in carpentry and obstinately finds a way around his town’s bureaucratic impediments. And I could also be the witty, older woman, who delights in her husband’s body and continues to cut his hair and is going to be cherished and properly cared for as long as he lives.

A fantasy? Heaven help us if this is not a true story.

© 2013 Margaret Morganroth Gullette

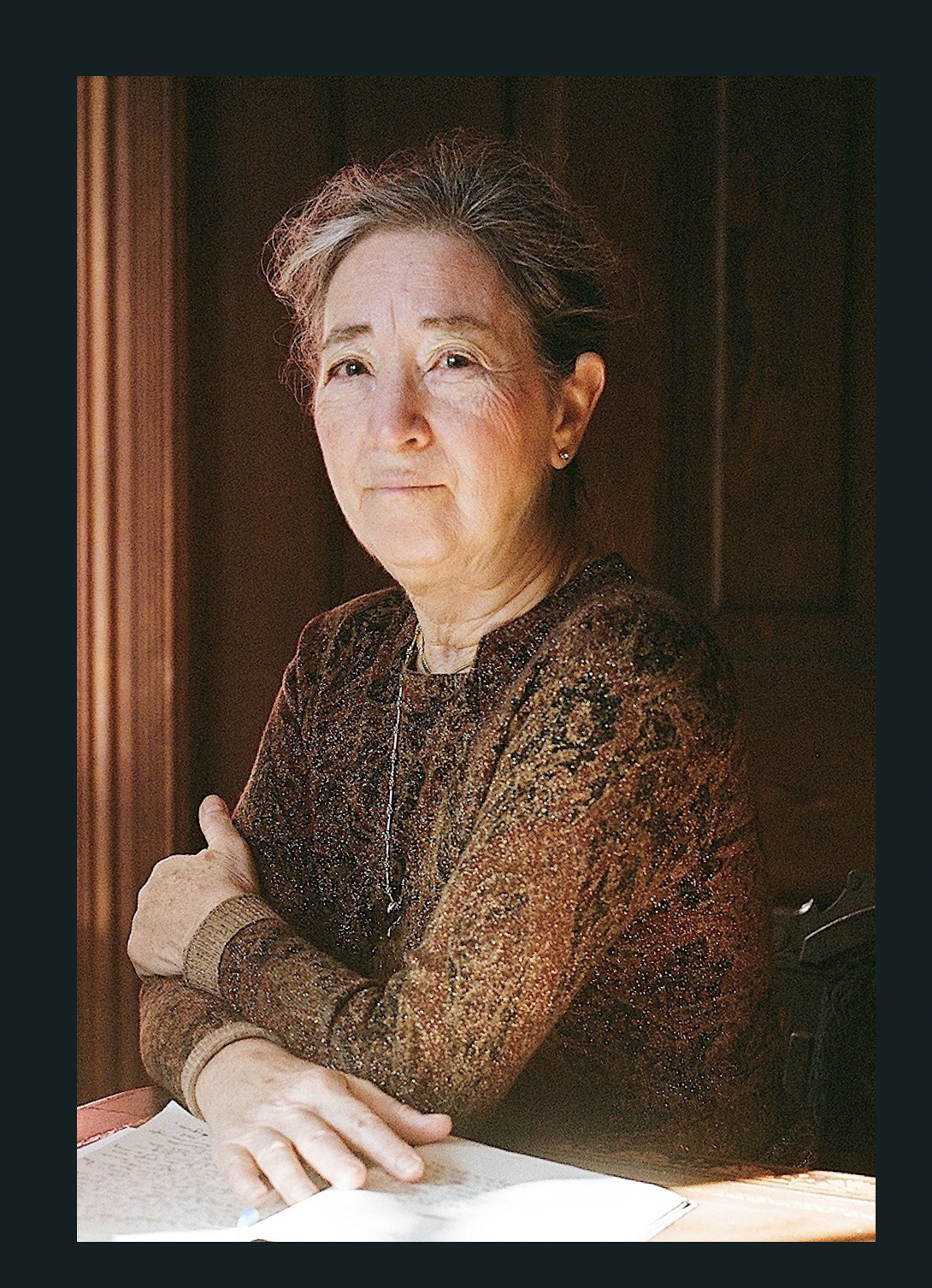

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.