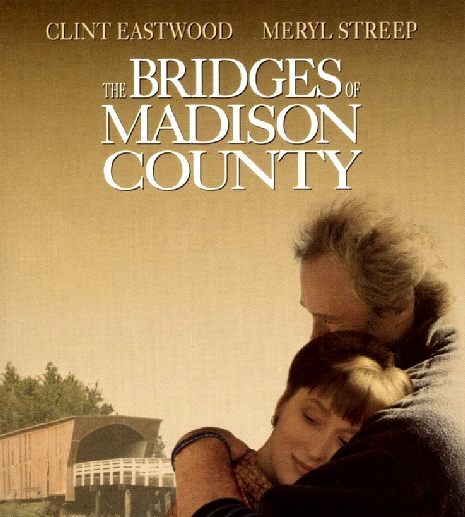

1995, USA, 135 min.

In dusty, sun-baked Iowa, National Geographic photographer Robert Kincaid (Clint Eastwood, who also directed) meets Francesca Johnson (Meryl Streep), a bored, stranded housewife. From their chance encounter—he stops at her house for directions—a tumultuous, four-day romance erupts. The emotionally authentic performances by the iconic actors are reason enough to watch. It’s the story’s structure, however—Francesca’s adult children relive the long-ago events through their late mother’s detailed journals—that makes us realize that older figures have unexpected depth and poetry to their lives. Our parents, it turns out, were people with churning emotions, a fact Bridges of Madison County reveals with resonance and poignancy.