Access to technology can make a huge difference to vulnerable elders isolated by COVID-19. Many don’t have access. Judith Graham explains why and explores creative solutions in this article written for Kaiser Health News (KHN). Graham’s piece was posted on the KHN website on July 24, 2020, and also ran on CNN.

Family gatherings on Zoom and FaceTime. Online orders from grocery stores and pharmacies. Telehealth appointments with physicians.

These have been lifesavers for many older adults staying at home during the coronavirus pandemic. But an unprecedented shift to virtual interactions has a downside: large numbers of seniors are unable to participate.

Among them are older adults with dementia (14 percent of those 71 and older), hearing loss (nearly two-thirds of those 70 and older) and impaired vision (13.5 percent of those 65 and older), who can have a hard time using digital devices and programs designed without their needs in mind. (Think small icons, difficult-to-read typefaces, inadequate captioning, among the hurdles.)

Many older adults with limited financial resources also may not be able to afford devices or the associated internet service fees. (Half of seniors living alone and 23 percent of those in two-person households are unable to afford basic necessities.) Others are not adept at using technology and lack the assistance to learn.

During the pandemic, which has hit older adults especially hard, this divide between technology “haves” and “have-nots” has serious consequences.

Older adults in the “haves” group have more access to virtual social interactions and telehealth services, and more opportunities to secure essential supplies online. Meanwhile, the “have-nots” are at greater risk of social isolation, forgoing medical care and being without food or other necessary items.

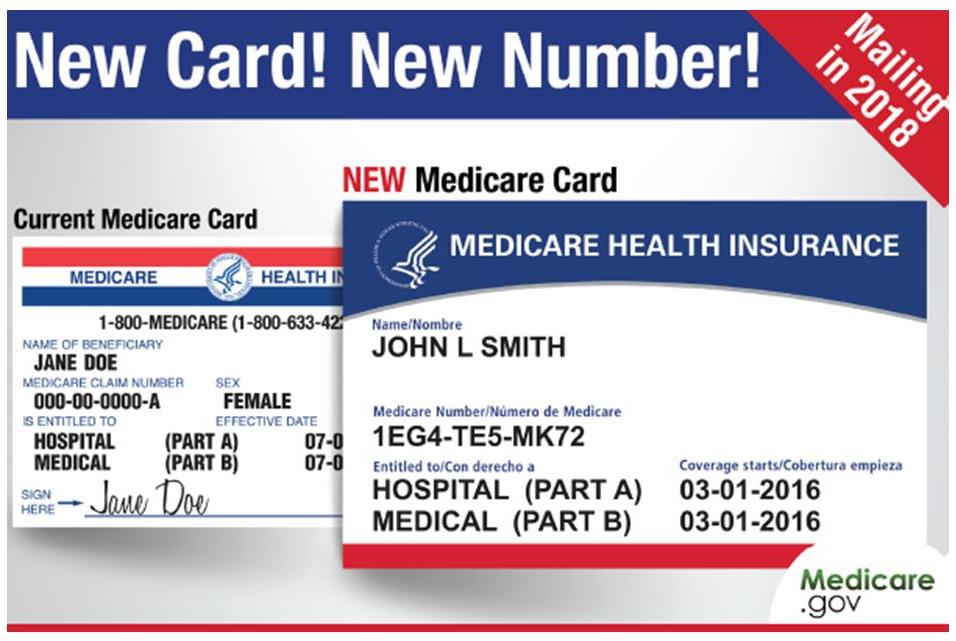

A Medicare Advantage plan found that about a third of its most vulnerable members couldn’t manage a telehealth appointment because they didn’t have the technology.

Dr. Charlotte Yeh, chief medical officer for AARP Services, observed difficulties associated with technology this year when trying to remotely teach her 92-year-old father how to use an iPhone. She lives in Boston; her father lives in Pittsburgh.

Yeh’s mother had always handled communication for the couple, but she was in a nursing home after being hospitalized for pneumonia. Because of the pandemic, the home had closed to visitors. To talk to her and other family members, Yeh’s father had to resort to technology.

But various impairments got in the way: Yeh’s father is blind in one eye, with severe hearing loss and a cochlear implant, and he had trouble hearing conversations over the iPhone. And it was more difficult than Yeh expected to find an easy-to-use iPhone app that accurately translates speech into captions.

Often, family members would try to arrange Zoom meetings. For these, Yeh’s father used a computer but still had problems because he could not read the very small captions on Zoom. A tech-savvy granddaughter solved that problem by connecting a tablet with a separate transcription program.

When Yeh’s mother, who was 90, came home in early April, physicians treating her for metastatic lung cancer wanted to arrange telehealth visits. But this could not occur via cell phone (the screen was too small) or her computer (too hard to move it around). Physicians could examine lesions around the older woman’s mouth only when a tablet was held at just the right angle, with a phone’s flashlight aimed at it for extra light.

“It was like a three-ring circus,” Yeh said. Her family had the resources needed to solve these problems; many do not, she noted. Yeh’s mother passed away in July; her father is now living alone, making him more dependent on technology than ever.

When SCAN Health Plan, a Medicare Advantage plan with 215,000 members in California, surveyed its most vulnerable members after the pandemic hit, it discovered that about one-third did not have access to the technology needed for a telehealth appointment. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had expanded the use of telehealth in March.

Other barriers also stood in the way of serving SCAN’s members remotely. Many people needed translation services, which are difficult to arrange for telehealth visits. “We realized language barriers are a big thing,” said Eve Gelb, SCAN’s senior vice president of health care services.

One alternative is a tablet already loaded with apps designed for adults 75 and older.

Nearly 40 percent of the plan’s members have vision issues that interfere with their ability to use digital devices; 28 percent have a clinically significant hearing impairment.

“We need to target interventions to help these people,” Gelb said. SCAN is considering sending community health workers into the homes of vulnerable members to help them conduct telehealth visits. Also, it may give members easy-to-use devices, with essential functions already set up, to keep at home, Gelb said.

Landmark Health serves a highly vulnerable group of 42,000 people in 14 states, bringing services into patients’ homes. Its average patient is nearly 80 years old, with eight medical conditions. After the first few weeks of the pandemic, Landmark halted in-person visits to homes because personal protective equipment, or PPE, was in short supply.

Instead, Landmark tried to deliver care remotely. It soon discovered that fewer than 25 percent of patients had appropriate technology and knew how to use it, according to Nick Loporcaro, the chief executive officer. “Telehealth is not the panacea, especially for this population,” he said.

Landmark plans to experiment with what he calls “facilitated telehealth”: nonmedical staff members bringing devices to patients’ homes and managing telehealth visits. (It now has enough PPE to make this possible.) And it too is looking at technology that it can give to members.

One alternative gaining attention is GrandPad, a tablet loaded with senior-friendly apps designed for adults 75 and older. In July, the National PACE Association, whose members run programs providing comprehensive services to frail seniors who live at home, announced a partnership with GrandPad to encourage adoption of this technology.

“Everyone is scrambling to move to this new remote-care model and looking for options,” said Scott Lien, the company’s co-founder and chief executive officer.

Nursing homes, assisted living centers and senior communities need to install communitywide Wi-Fi services.

PACE Southeast Michigan purchased 125 GrandPads for highly vulnerable members after closing five centers in March where seniors receive services. The devices have been “remarkably successful” in facilitating video-streamed social and telehealth interactions and allowing nurses and social workers to address emerging needs, said Roger Anderson, senior director of operational support and innovation.

Another alternative is technology from iN2L (an acronym for It’s Never Too Late), a company that specializes in serving people with dementia. In Florida, under a new program sponsored by the state’s Department of Elder Affairs, iN2L tablets loaded with dementia-specific content have been distributed to 300 nursing homes and assisted living centers.

The goal is to help seniors with cognitive impairment connect virtually with friends and family and engage in online activities that ease social isolation, said Sam Fazio, senior director of quality care and psychosocial research at the Alzheimer’s Association, a partner in the effort. But because of budget constraints, only two tablets are being sent to each long term care community.

Families report it can be difficult to schedule adequate time with loved ones when only a few devices are available. This happened to Maitely Weismann’s 77-year-old mother after she moved into a short-staffed, Los Angeles, memory-care facility in March. After seeing how hard it was to connect, Weismann, who lives in Los Angeles, gave her mother an iPad and hired an aide to ensure that mother and daughter were able to talk each night.

Without the aide’s assistance, Weismann’s mother would end up accidentally pausing the video or turning off the device. “She probably wanted to reach out and touch me, and when she touched the screen it would go blank and she’d panic,” Weismann said.

What’s needed going forward? Laurie Orlov, founder of the blog Aging in Place Technology Watch, said nursing homes, assisted living centers and senior communities need to install communitywide Wi-Fi services—something that many lack.

“We need to enable Zoom get-togethers. We need the ability to put voice technology in individual rooms, so people can access Amazon Alexa or Google products,” she said. “We need more group activities that enable multiple residents to communicate with each other virtually. And we need vendors to bundle connectivity, devices, training and service in packages designed for older adults.”

Judith Graham writes a column on aging and health for KFF Health News, where she’s a contributing columnist. She also freelances for other publications. Earlier in her career, Judith contributed more than 80 pieces to the New York Times blog, The New Old Age. She was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for a series on defective pacemakers and was part of a Chicago Tribune team that won a Pulitzer in 2001.