Journalist Bruce Horovitz asked four experts in geriatrics to explain what normal aging is apt to be like for people who have taken care of their health. The experts discuss the physiological changes that typically occur, from our 50s through our 90s. Kaiser Health News (KHN) posted Horovitz’s article on April 11, 2018. It also ran in USA Today.

For 93-year-old Joseph Brown, the clearest sign of aging was his inability the other day to remember he had to have his pants unzipped to pull them on.

For 95-year-old Caroline Mayer, it was deciding at age 80 to put away her skis, after two hip replacements.

And for 56-year-old Thomas Gill, MD, a geriatrics professor at Yale University, it’s accepting that his daily five-and-a-half-mile jog now takes him upward of 50 minutes—never mind that he long prided himself on running the distance in well under that time.

Is there such a thing as normal aging?

The physiological changes that occur with aging are not abrupt, said Gill.

The changes happen across a continuum as the reserve capacity in almost every organ system declines, he said. “Think of it, crudely, as a fuel tank in a car,” said Gill. “As you age, that reserve of fuel is diminished.”

Drawing on their decades of practice, along with the latest medical data, Gill and two geriatric experts agreed to help identify examples of what are often—but not always—considered to be signposts of normal aging for folks who practice good health habits and get recommended preventive care.

The 50s: Stamina Declines

Gill recognizes that he hit his peak as a runner in his 30s and that his muscle mass peaked somewhere in his 20s. Since then, he said, his cardiovascular function and endurance have slowly decreased. He’s the first to admit that his loss of stamina has accelerated in his 50s. He is reminded, for example, each time he runs up a flight of stairs.

In your 50s, it starts to take a bit longer to bounce back from injuries or illnesses, said Stephen Kritchevsky, PhD, 57, an epidemiologist and co-director of the J. Paul Sticht Center for Healthy Aging and Alzheimer’s Prevention at Wake Forest University. While our muscles have strong, regenerative capacity, many of our organs and tissues can only decline, he said.

Times change. Many people today function as well in their mid-70s as those in their mid-60s did a generation ago.

David Reuben, MD, 65, experienced altitude sickness and jet lag for the first time in his 50s. To reduce those effects, Reuben, director of the Multicampus Program in Geriatrics Medicine and Gerontology and chief of the geriatrics division at UCLA, learned to stick to a regimen—even when he travels cross-country: he tries to go to bed and wake up at the same time, no matter what time zone he’s in.

There often can be a slight, cognitive slowdown in your 50s too, said Kritchevsky. As a specialist in a profession that demands mental acuity, he said, “I feel I can’t spin quite as many plates at the same time as I used to.” That, he said, is because cognitive-processing speeds typically slow with age.

The 60s: Susceptibility Increases

There’s a good reason why even healthy folks age 65 and up are strongly encouraged to get vaccines for flu, pneumonia and shingles: humans’ susceptibility and negative response to these diseases increase with age. Those vaccines are critical as we get older, Gill said, since these illnesses can be fatal—even for healthy seniors.

Hearing loss is common, said Kritchevsky, especially for men.

Reaching age 60 can be emotionally trying for some, as it was for Reuben, who recalls 60 “was a very tough birthday for me. Reflection and self-doubt is pretty common in your 60s,” he said. “You realize that you are too old to be hired for certain jobs.”

The odds of suffering some form of dementia double every five years beginning at age 65, said Gill, citing an American Journal of Public Health report. While it’s hardly dementia, he said, people in their 60s might begin to recognize a slowing of information retrieval. “This doesn’t mean you have an underlying disease,” he said. “Retrieving information slows down with age.”

The 70s: Chronic Conditions Fester

Many folks in their mid-70s function as folks did in their mid-60s just a generation ago, said Gill. But this is the age when chronic conditions—like hypertension or diabetes or even dementia—often take hold. “A small percentage of people will enter their 70s without a chronic condition or without having some experiences with serious illness,” he said.

People in their 70s are losing bone and muscle mass, which makes them more susceptible to sustaining a serious injury or fracture in the event of a fall, Gill added.

Seventies is the pivotal decade for physical functioning, said Kritchevsky. Toward the end of their 70s, many people start to lose height, strength and weight. Some people report problems with mobility, he said, as they develop issues in their hips, knees or feet.

Most older people—including those in their 90s and beyond—are more satisfied with their lives than younger people are.

At the same time, roughly half of men age 75 and older experience some sort of hearing impairment, compared with about 40 percent of women, said Kritchevsky, referring to a 2016 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Another conundrum common to the 70s: people tend to take an increasing number of medications used for “preventive” reasons. But these medications are likely to have side effects on their own or in combination, not all of which are predictable, said Gill. “Our kidneys and liver may not tolerate the meds as well as we did earlier in life,” he said.

Perhaps the biggest emotional impact of reaching age 70 is figuring out what to do with your time. Most people have retired by age 70, said Reuben, “and the biggest challenge is to make your life as meaningful as it was when you were working.”

The 80s: Fear of Falling Grows

Fear of falling—and the emotional and physical blowback from a fall—are part of turning 80.

If you are in your 80s and living at home, the chance that you might fall in a given year grows more likely, said Kritchevsky. About 40 percent of folks 65 and up who are living at home will fall at least once each year, and about 1 in 40 of them will be hospitalized, he said, citing a study from the UCLA School of Medicine and Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center. The study notes that the risk increases with age, making people in their 80s even more vulnerable.

By age 80, folks are more likely to spend time in the hospital—often due to elective procedures such as hip or knee replacements, said Gill, basing this on his own observations as a geriatric specialist. Because of diminished reserve capacities, it’s also tougher to recover from surgery or illnesses in your 80s, he said.

The 90s & Up: Relying on Others

By age 90, people have roughly a one-in-three chance of exhibiting signs of dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease, said Gill, citing a Rush Institute for Healthy Aging study. The best strategy to fight dementia isn’t mental activity but at least 150 minutes per week of “moderate” physical activity, he said. It can be as simple as brisk walking.

At the same time, most older people—even into their 90s and beyond—seem to be more satisfied with their lives than are younger people, said Kritchevsky.

At 93, Joseph Brown understands this—despite the many challenges he faces daily. “I just feel I’m blessed to be living longer than the average Joe,” he said.

Brown lives with his 81-year-old companion, Marva Grate, in the same, single-family home that Brown has owned for 50 years in Hamden, CT. The toughest thing about being in his 90s, he said, is the time and thought often required to do even the simplest things. “It’s frustrating at times to find that you can’t do the things you used to do very easily,” he said. “Then, you start to question your mind and wonder if it’s operating the way it should.”

Brown, a former maintenance worker who turned 85 in May, said he gets tired—and out of breath—very quickly from physical activity.

He spends ample time working on puzzle books, reading and sitting on the deck, enjoying the trees and flowers. Brown said no one can really tell anyone else what “normal” aging is.

Nor does he claim to know himself. “We all age differently,” he said.

Brown said he doesn’t worry about it, though. “Before the Man Upstairs decides to call me, I plan to disconnect the phone.”

KHN’s coverage of these topics is supported by John A. Hartford Foundation, Gordon and Betty Moor Foundation and the Scan Foundation.

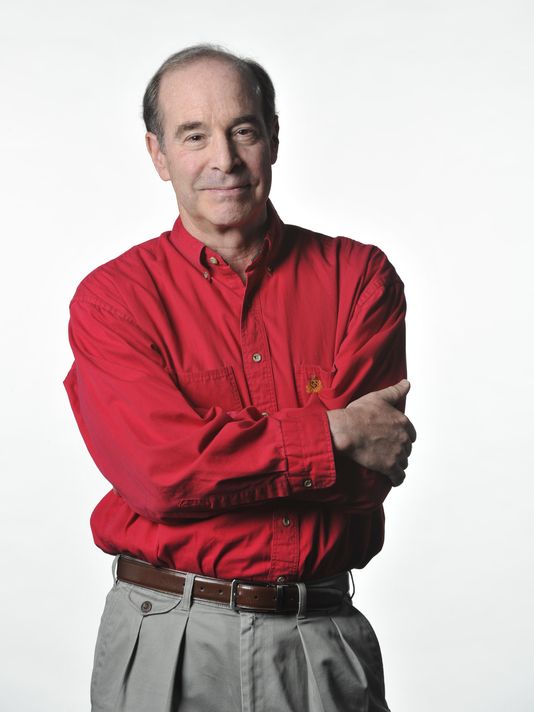

Freelance journalist Bruce Horovitz writes regularly for Kaiser Health News and other publications, including the Washington Post and AARP The Magazine. He was a marketing reporter for USA Today for 20 years and wrote a column on marketing for the Los Angeles Times for a decade.