Every year, millions of older adults roll up their sleeves for an annual physical. Blood is drawn, a cuff tightens around the arm, and a stethoscope taps against the chest. A few days later, a patient portal pings with test results, unleashing a barrage of numbers: cholesterol levels, blood pressure readings, blood glucose, creatinine and more.

It’s like receiving a report card in a language you don’t speak.

What do all these numbers mean? Is it important for patients to understand and track them from one year to the next? And if a lab test produces an abnormal result, should you worry, wait or push your physician for action?

“There are so many tests out there that it’s very confusing for patients,” acknowledged Darshan Kapadia, MD, senior internist at Texas Health Plano in Plano, TX.

Understanding your numbers can help you ask informed questions, advocate for your own health care and partner more effectively with your health care provider. At the same time, health care professionals caution, it’s important to put numbers in context. No single lab result tells the whole story. And determining what’s normal for each patient’s personal health situation is more complicated than it looks. Numbers alone don’t determine diagnoses; they’re data points that must be weighed along with a patient’s health history and physical exam.

“There’s more to the story than just those numbers on the lab sheet,” said Rebekah Mulligan, MD, an internal and geriatric medicine physician at Texas Health Harris Methodist Hospital in Southlake, TX.

More Isn’t Always Better

Understanding your personal numbers is more important than ever, now that many patients have direct access to test results. The growth in health information technology, especially patient portals, means more and more data is relayed straight to patients, sometimes in bewildering detail, often without medical guidance.

But more information isn’t always a good thing. This windfall of data to patients comes at a time when primary care physicians are increasingly in short supply and pressed for time to explain those results.

“Clinicians have expressed concern that patients often experience great difficulty in comprehending, interpreting, and correctly responding to personalized health information,” according to a 2020 study published in the Israel Journal of Health Policy Research. “In particular, misunderstanding test results leads to confusion, frustration, and disruptions in healthcare processes, including delays in seeking care, overutilization of services, medication errors, and inappropriate healthcare decision-making.”

At the same time, in most states, patients can now take advantage of “DIY diagnostics” by ordering their own blood tests at medical labs, without guidance or orders from medical professionals. At-home medical and wellness testing is exploding; it’s now a $5 billion market in the United States.

Advocates say this expanded pool of available information gives patients more options when they’re looking for answers to hard-to-diagnose health issues or waiting for months for medical appointments. But medical professionals argue that it can be risky for patients to interpret their own results. Some may panic over an out-of-normal-range result that isn’t necessarily concerning—or assume that a blood workup with only normal results means they’re healthy.

Normal vs. Abnormal

In reviewing their lab results, one common assumption many patients make is viewing the numbers as either “normal” or “abnormal.” But physicians take a more nuanced view. Even the term “normal” can be misleading.

“It’s important for patients to understand how the medical profession comes up with what is considered the normal range,” said Diana Cardona, MD, professor and chair of the department of pathology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine. For example, a white blood count (WBC) of 4,500—11,000 cells/mcL is considered within normal range. Researchers developed that range by looking at data from large groups of healthy individuals. The range of numbers where 95 percent of those patients landed is designated as normal.

“But that’s really just a statistical number,” Cardona said. “There’s the 5 percent on either end of the range who are still healthy people, but now we’ve called them abnormal.”

Cardona prefers the term “reference range” rather than “normal range” for that 95 percent.

Context is important too. Two patients with the same borderline cholesterol numbers, for example, might need totally different treatment approaches.

“If a patient has diabetes and high blood pressure, I need them at a much lower cholesterol level to control their risk, compared to a patient without diabetes or high blood pressure,” said Donald Lloyd-Jones, MD, director of the Framingham (MA) Center for Population and Prevention Science and chief of preventive medicine at the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center.

Doctors take into account how much a number on a test changes from year to year and how quickly.

Almost every number comes with asterisks—exceptions to the rule when it comes to interpretation. Body mass index (BMI) seems like a straightforward way to determine whether a patient is at a healthy weight: a BMI of 19-24 is considered healthy; 25 or higher is overweight; over 30 is obese.

But according to the American Heart Association, a BMI number should be “interpreted with caution” among persons of Asian ancestry, older adults and muscular individuals. For adults 65 and older, recent studies link somewhat higher BMI numbers to better health and higher chances of survival. Similarly, a weight lifter with very little body fat could have a higher body weight that yields a BMI that labels them “obese.” The Heart Association also recommends factoring in waist circumference, which helps determine how much body fat has accumulated around the middle section, which is associated with higher cardiovascular risk.

Doctors also look at individual trends—how much a number changes, and how quickly, from one year to the next. That can be especially important for lab tests like the prostate specific antigen (PSA), which helps detect prostate cancer in men.

“It’s really important to keep an eye on the rate of change,” Mulligan said. “Say you go to a new doctor, and you have some abnormal numbers. The doctor will want to know, ‘Is this where you’ve always been, or is this a new thing?’ Because if it’s a new thing, it’s a bigger deal in some instances.”

Tracking Your Numbers

Any time new test results come in, Kapadia goes over the written report and encourages the patient to scan or photograph the report for their own records. Keeping track of your numbers can prove useful in a medical emergency or if you change providers.

“Have a folder somewhere in your cell phone titled, ‘My health record’ and keep your reports in there,” he advised. “Then make sure you can find it in your phone—not in the cloud—so that you don’t need the internet to retrieve the information. So, if you’re traveling, and, say, you’re on a safari in Africa and something happens, you’ve got the data to look at right there. You don’t have to remember it or understand it, because the physician on duty can review it from your phone.”

Patients can also take advantage of a growing body of tools designed to help patients interpret their own key medical metrics in context. Lloyd-Jones and the American Heart Association created Life’s Essential 8, a checklist to help patients understand key numbers (cholesterol, blood pressure, blood sugar and body weight) in combination with lifestyle factors (exercise, sleep, diet and nicotine exposure) to assess and manage their cardiovascular health. The American Heart Association also offers “Know Your Numbers” fact sheets for patients with diabetes and for women concerned about their heart health.

Researchers are also working on making the lab results and other reports easier for patients to understand. Cardona is part of a College of American Pathologists research project exploring ways to make pathology reports more patient-friendly. In focus groups with cancer patients, she was surprised to learn that they didn’t want the information summarized in plain language. Learning the medical terminology helped them speak more easily with their care team. But they did want more explanation, such as a glossary of terms.

Handling Abnormal Results

If a number is somewhat out of normal range, and your physician says, “Don’t worry” or “Let’s wait and see,” should you question that?

“That’s the art of medicine—understanding when those red flags are a big deal and when they’re not,” said Mulligan. “Sometimes patients can get hung up on an [out-of-range result] and ask for more intense testing that’s not clinically applicable. I try to explain why that number is OK in this situation.”

But tell your doctor if a test result worries you, Mulligan added.

“Keep asking questions,” she said. “You can say, ‘I hear what you’re saying, and I’m not trying to second-guess you, but can you show me what it says in the literature so that I can educate myself?’ I would much rather have a patient do that than worry for the next 12 months.”

Remember that any lab result is a snapshot of a particular day and time. Many factors can skew the results of a test on a particular day. An abnormal kidney function number might indicate the patient has kidney disease—or is mildly dehydrated, which is common in hot weather. Certain medications or supplements may affect the results of kidney or liver function tests. Mulligan often sees that in patients who take biotin or hair-growth supplements like Nutrafol.

When is blood pressure too low? There’s no accepted number. Low blood pressure is diagnosed by symptoms instead.

“That’s why it’s so important to tell your physician if you’re taking anything—including supplements or over-the-counter medications—that may not be on your medications list,” Mulligan said. “And don’t assume the information in the [medical practice’s] computer is up to date. Always bring a written list to your appointment.”

Conversely, understand that even a complete battery of tests with entirely normal results doesn’t guarantee that a patient is healthy. Kapadia recently diagnosed a patient with lymphoma; that patient’s blood work was 100 percent normal. An imaging test revealed the presence of cancer.

Also, know that some numbers have clear cut-off levels; others do not.

“Optimal blood pressure is defined as less than 120 on the top number and less than 80 on the bottom number,” said Lloyd-Jones. “But there’s no hard-and-fast number for blood pressure that’s too low. For many patients, a top number in the 90s may be normal and healthy and certainly means they’re at lower risk for strokes or heart failure. But if the patient gets light-headed when they stand up, that’s too low for them. The lower limit on blood pressure is defined by symptoms rather than a specific number.”

Changing Interpretations

Another caveat: as new research emerges, medicine changes. For example, the numbers you’ve heard for years for healthy cholesterol levels may no longer apply.

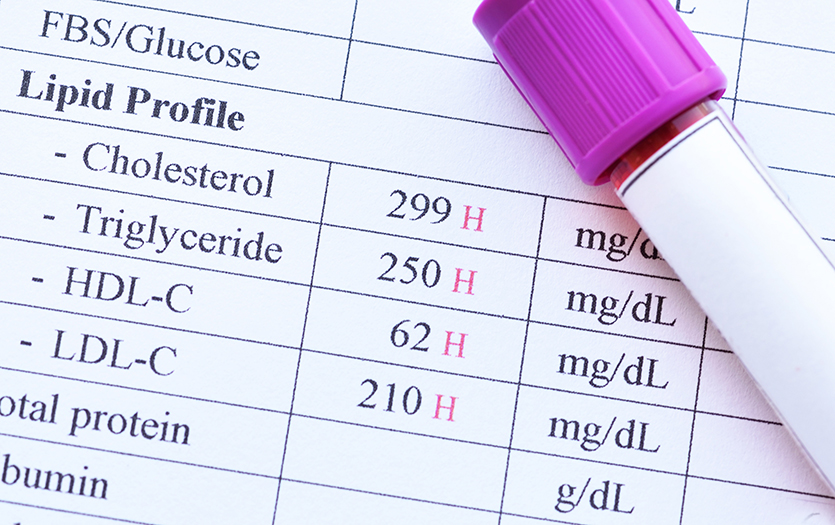

Until recently, physicians typically assessed cardiovascular health with a lipid panel that calculated total cholesterol as a combination of “good” (HDL) and “bad” (LDL) cholesterol along with triglycerides. Today, those numbers are still considered, but as part of more-complex algorithms that also factor in other metrics (such as blood sugar and blood pressure) as well as gender, age, smoking status and family history in determining whether to prescribe medications for high cholesterol or high blood pressure.

“We want the LDL to be as low as possible, but we’ve de-emphasized HDL as a target of therapy, because medications don’t really help move that number,” Lloyd-Jones said. “And there’s more focus on triglycerides, which are more sensitive to diet and exercise and a better indicator of current metabolic health.”

That complexity makes it even more important for patients to ask questions and engage in back-and-forth as needed with their primary care physicians.

“A good relationship with your physician is worth its weight in gold,” said Kapadia. “That’s why it’s so important to find someone you like and trust and to start developing that relationship with them. So you can work together to understand and personalize those numbers for your own situation.”

Freelance writer Mary Jacobs lives in Plano, TX, and covers health and fitness, spirituality, and issues relating to older adults. She writes for the Dallas Morning News, the Senior Voice, Religion News Service and other publications; her work has been honored by the Religion Communicators Council, the Associated Church Press and the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Visit www.MaryJacobs.com for more.