My two sisters, two brothers and I knew our mother’s condition was terminal. Together with her, we gathered to have a painful conversation about her final wishes. Grieving for a loved one is acutely hard enough; the last thing anyone wants to do just after the loss is sit across from a funeral director, rushed, making high-pressure, expensive choices.

Funeral homes provide essential services, but they are also profit-driven businesses. Staff may try to sell products and services you do not want or need or that you can’t afford. Most funerals and burial arrangements in the United States cost between $7,000 and $10,000, with cremation slightly less. Averages are broken down by state here. There is nothing wrong with an expensive funeral if that’s what the family wants. But many families who might prefer (or need) a simple, dignified ceremony can end up with something lavish and costly and live to regret it.

After Mom died, my older brother and I went to the funeral home she chose. We picked a casket, the date and times for the viewing and arranged for the priest Mom liked at the chapel where she worshiped. We gave the funeral home the outfit Mom chose and called the loved ones she wanted to participate in the service. It was lovely, and we knew it was what she wanted.

Fast-forward a year and a half, and my husband died suddenly. He had cardiac issues complicated by insulin-dependent diabetes. I should have been more prepared, but sadly, indefensibly, I was not.

I did what every guide tells you not to do. I went to the funeral home alone; I did not take along a companion to assure me that sensible, cost-saving decisions are OK. Unaware of the extent to which I’d now be living with crippling medical debt and the loss of the primary breadwinner’s salary, I still had the wherewithal to ask about the cost of what they recommended, to make choices based on price. But it made me feel cold and uncaring.

I opted for cremation but still had the menu of services that are standard practice. I learned that I’d have to pay for transportation from the morgue, and every day his body was stored would be an additional cost. I had to rent the parlor for the mourners for a fee based on how many people I expected. How would I know? The newspapers carried obituaries, but they charged by the line, so my husband’s was brief and not at all what I wanted. Add to the bill the cost of transportation to the crematorium and the actual cremation. We’re not religious; there was no ceremony.

In the fog of grief, I made no arrangements for anyone after the viewing. I took some criticism for that later, but it was what it was. I had two children to get to school the next day, and they were my singular focus. No one offered to counsel me and help me navigate the funeral world or even ask me if they could buy a tray of sandwiches.

The key here is to plan in advance. And while it can be difficult, preplanning your own funeral is sensible and gives valuable input to your survivors when they are forced to make many decisions on short notice.

Write down and share your preferences with loved ones and include them in the process to make sure their emotional needs are met. When we had the family sit-down, my mother said she didn’t care if she was cremated or not. My sisters said they wanted Mom buried along with my father. Decision made.

If you decide to go the traditional route with a funeral home, start by asking for its general price list in writing. The Federal Trade Commission requires funeral homes to provide a copy of their prices if you ask. Some funeral directors may encourage you to come in person. Deal only with funeral homes that readily supply detailed pricing information without requiring an in-person appointment.

Many funeral homes push plans that let you prepay for your funeral. These agreements represent significant financial commitments, and many unscrupulous places have not protected their customers’ (prepaid) wishes. A better arrangement is to open a joint savings account with a likely survivor who will get immediate access to the funds upon your death. I have a small insurance policy earmarked for funeral costs.

There are several options for handling remains, such as burial with a traditional funeral, immediate burial, or cremation (with or without a funeral). I opted to cremate my husband’s remains. With my mother, we chose burial. It required a casket, a cemetery plot, fees to open and close the grave, cemetery upkeep, and a headstone. Needless to say, we didn’t “shop around.” We simply went to the monument business recommended by the funeral director.

I learned that, for cost saving, immediate burial with a basic casket is the practical choice. A funeral home files the necessary paperwork, places the unembalmed body in a casket and takes the remains to a cemetery in one day, without services.

Cremation is an increasingly popular choice. Like burial, it can be direct or after a funeral service. Cremation and immediate burial allow flexibility in the timing and location of services; many families now hold memorial services in a place of their choosing. Cremated remains may be scattered, kept at home, buried in a cemetery or interred in a columbarium. Burial of remains adds to the cost.

You’ll want to make your wishes known to loved ones, your choice between a religious and secular service and where it will be held, along with any other requests. I can oversimplify my own cavalier approach by saying, “I don’t care, I’ll be dead.” But I’m woefully behind on identifying my own end-of-life wishes, despite being immensely grateful to my mother for spelling out her wishes and so remorseful about how I handled my husband’s celebration of life. It’s high time I let my daughters know what I’d like. In the end, it will be my last gift to them.

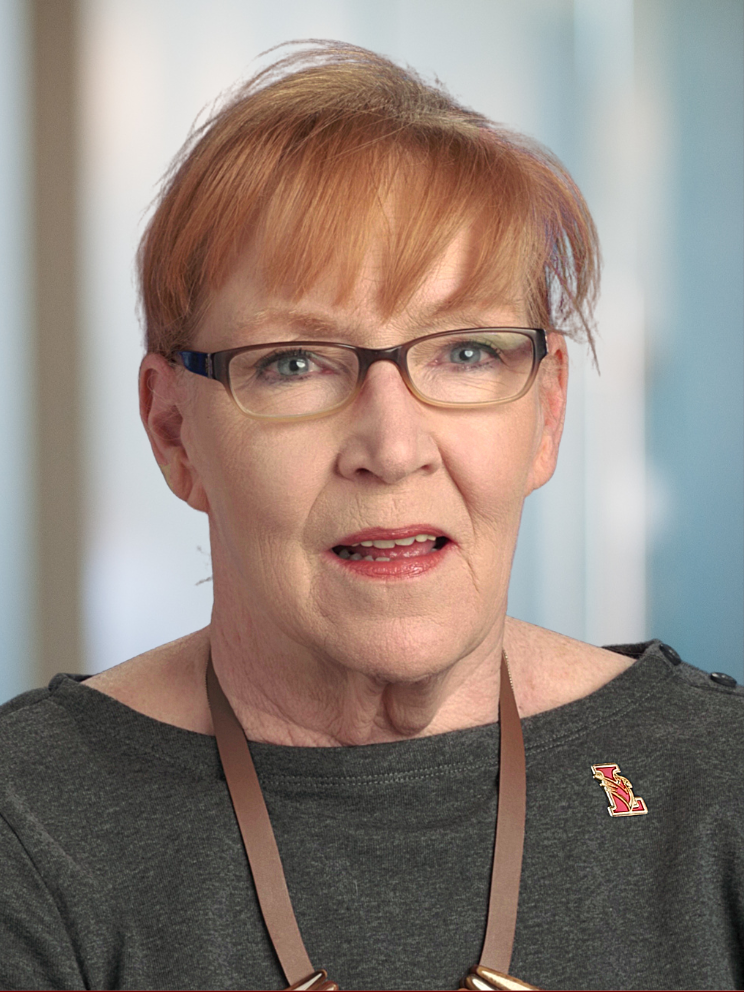

Pepper Evans works as an independent-living consultant, helping older adults age in place. She is the empty-nest mother of two adult daughters and has extensive personal and professional experience as a caregiver. She has worked as a researcher and editor for authors and filmmakers. She also puts her time and resources to use in the nonprofit sector and serves on the Board of Education in Lawrence Township, NJ.