Last year, it finally became obvious that we needed ramps at our summer cabin on Sawdy Pond.

The architectural part was straightforward, but it turned out we needed self-examination and conviction to solve a deeper problem.

The acres we own in a wilderness of Massachusetts oak, beech and tupelo forest are covered with different kinds of ancient loam, and hidden underneath the rich, millennial soil is another gift, a warehouse of granite. A glacier that pushed a massive moraine ahead of it, from north to south, stopped on our property. Everywhere you dig, you find stony treasure. Digging foundations for the bedrooms, the excavator mined gorgeous hunks of granite with veins of white, pink or yellow: smoothly rounded, precious. They’re of the land, natural and cost-free, everywhere.

Decades ago my husband and I built the broad, wooden decks that let us look over the lake from a small height. To move from lookout to lawn and lake, instead of poky wooden stairs, the esthetically satisfying choice we made was to provide mainly flat-topped granite boulders of different heights. Our look was rustic.

For our deck foundations, I first spent some time collecting perfectly shaped granite rocks that I could lift by myself—one-woman stones. Our town is celebrated for its stone walls going back to the eighteenth century. By watching master craftsmen building new walls, I taught myself how to make these foundations. Filled with fortyish strength and ambition, I dug deep trenches. When I needed bigger rocks for stability two feet down, I had to heave some, end over end, up to the site. Mainly it takes patience and stamina, not brute strength, to fit the tricky angular corners first and then find the prettiest faces of the granite for show.

Fitting and finding gave me the most pleasure, but I mastered the skill of mortaring so that little cement shows on the outside. Inside the wall, massive dumps of concrete would hold the whole together forever. In all this time, no frost has heaved my foundations. Stone and mortar satisfy, lastingly. I felt I had joined in some small way the first Greeks and Egyptians who worked for keeps.

With time, however, the flat-topped boulders felt cruel sharp in places, not wearing down softly like marble does, and not entirely smooth to the tender foot. I like to go barefoot and I could scamper up and down familiarly, but even though we were esthetic idiots with tough feet, we foresaw we were going to have to move on this problem.

But we didn’t. Years went by, as they do in the forest and on the lake in the lazy summertimes, and we did nothing. We talked every so often about alternatives. Stairs! “Most people have stairs!” “Nah, tacky.” We just delayed, we forgot and delayed.

And then last summer I watched helplessly from too far away as our granddaughter, Tamo, almost three, fell down a step that was nearly as high as her waist. She didn’t bleed. She was shocked in her dignity and slowed down in her rush to join the fun on the lawn. Unfair to short persons.

That sentiment chimed with the well-founded observation that some of our friends have balance or walking issues. Some of our dearest cyborgs have bionic knees or hips. It is possible that we may too someday. We were thus inclining, birches bent by the wind but still vertical, toward accepting the concept of a ramp.

One day on a neighborhood walk in my suburb, I stopped to watch some carpenters make a handicap ramp for a local church. The structure seemed pretty simple. A gray-haired, heavyset man carrying a T square seemed the expert of the three. I asked him a few questions.

I walked home realizing how easy it would be for my husband and me to build a ramp ourselves at the cabin. David and I agreed on a modest one, three feet wide and ten feet long—a gentle walk down, not precipitous, nothing to tighten the core stomach muscles. We took on the ramp project ourselves. It turned out to be interesting, and the work went almost too quickly.

Hurrying up and down the ramp or sauntering easily down to the lawn with a tray of food for the picnic table, I immediately felt graceful and safe, rather than anxious and ungainly. My friend Marsha says she doesn’t like to feel “doddery” when mostly she thinks of herself as strong. I know what she means. With the ramp, I regained a sense of flexible strength that maneuvering cautiously up and down granite stones had been denying me. Yet in a funny way—precisely because I was so grateful for recovering my sense of agility—I was finally able to see the foolish, disquieting ageism and ableism behind our long delay. I observed this with some chagrin since I have been uncovering similar biases in my books and essays for years.

The truth was, we hadn’t confronted the need for a ramp head on. It seems obvious now. We had been happy enough owning the old cabin but we had unconsciously resisted turning it into “an old people’s home” that screamed out, as it were, “bodies with problems live here.” In our defense, we didn’t need any heartfelt, long talks to realize how wrong it is that people retain internalized, ageist ableism even when it goes against their best interests.

For us, the turning point psychologically came down to a practical matter: we felt capable enough to build the modest structure ourselves without much expense in money or heart’s ease. We are both in our late seventies. Decisions made in health and strength, without haste, with enthusiasm, with joy in the execution, are much easier than those made in a sudden, panicky emergency, as when a bad knee or a broken foot makes going up steps untenable. If only escaping ageism could always be acquired as smoothly as our ramp fit into our lives and spaces.

The ramp looks as if it has been there forever: clean, parallel lines, with the ancient rhododendron towering over one side, and a narrow carpet of low vinca on the other. Esthetically, the final need was for some deep reseeding in crab mulch at the bottom. It rained for three days and the grass I planted came up a healthy spring green.

Two friends who visited the cabin admired the ramp, so we enlarged a bit, as Mark Twain might say, on our building process. But I found recently, at a party in town, when I described the installation to younger people who hadn’t walked the walk, that the subtle boast about our prowess as manual laborers was undermined by our listeners’ obvious aversion to putting any darn ramp on their piece of high-priced real estate. Like a small, bad smell, a baby fart, they left the impression that such a structure would feel like a news crawl publicizing decrepitude.

So what David and I can accept for ourselves in the privacy of the deep woods still has worldly trouble attached to it beyond. And I myself, it must be said, am not rushing to put up a long ramp instead of the elegant, wide, wooden stairs on the front of our 1876 Victorian in town. In my thickly settled neighborhood, filled with people who support disability mitigations for sidewalks, schools, city hall, I don’t see a single ramp. Some of our neighbors may have the same problem we have, not wanting to be the first to advertise “old people live here.” It will take some bigger wind here—of collective taste, good sense and leadership—to dissipate ageist odors. Perhaps I should say I will lead the way, and maybe we will.

Architects like to say that any human problem can be solved by architecture. But some problems of human levelling also require love, amusement, introspection, concern, foresight, a little cash, a little muscle and a heap of social courage.

Now Tamo, age four, can run up and down the ramp. When the time comes, she will skateboard down its easy slope. Our friends who visit can feel safe and cared for. As for us, there in the woods, we have overcome some interfering ageism, the silly kind that keeps you from doing the right and necessary. We have joined the world of universal design.

Ramp up, ramp on. Let the wild rampus start.

Tamo will run up and down for years with no sense of the sharp-pointed arrow of time. That kind of awareness, like every other human invention of meaning, has to be learned. Meanwhile, imperceptibly—and so far, “So what?”—we adults, exulting in her agility, are ever so gently sliding down the ramp of life.

© 2019 Margaret Morganroth Gullette

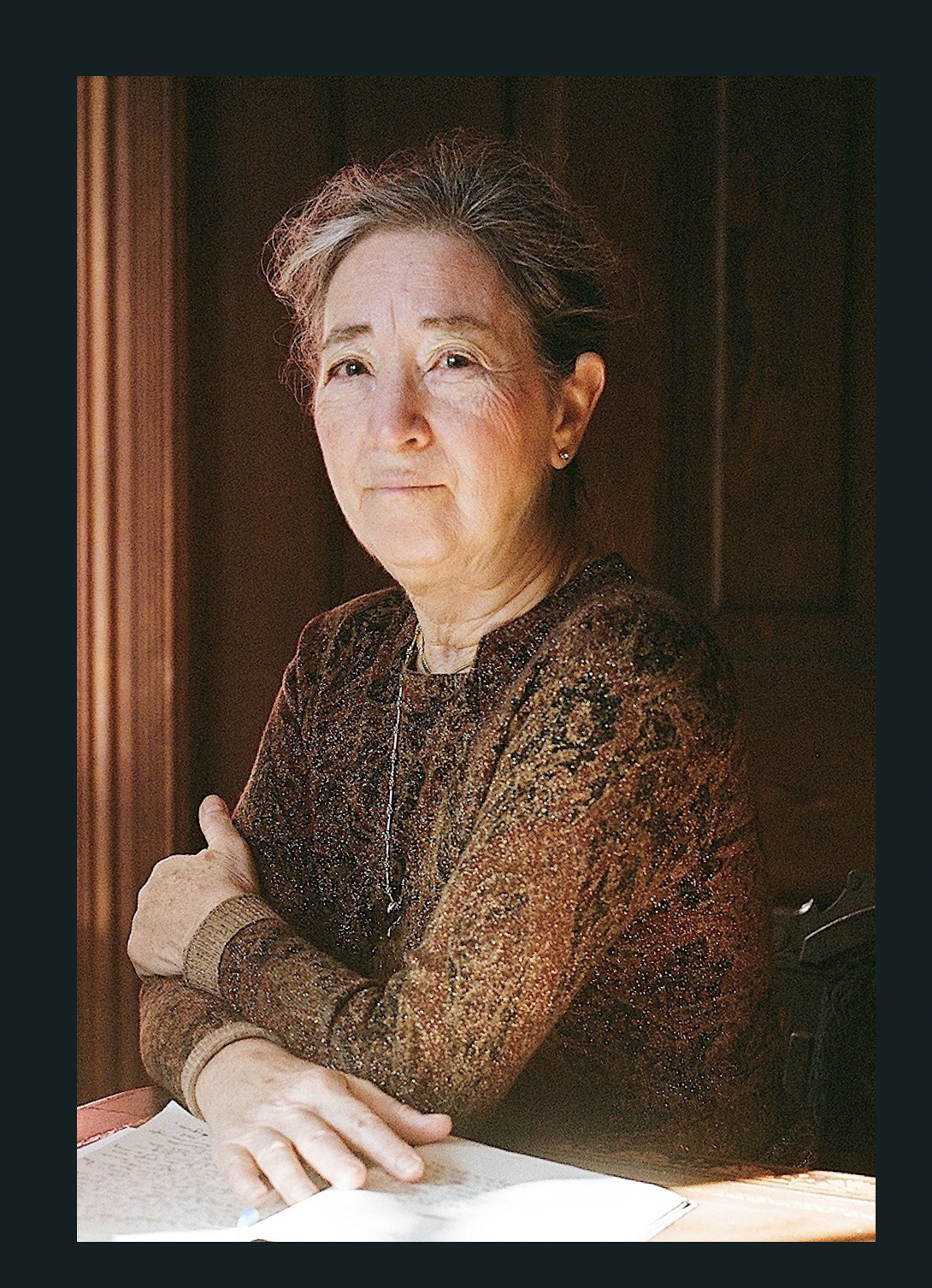

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.