I was delighted to see an editorial in the New York Times about a crisis in the making, the growing shortage of geriatricians. (Geriatricians are doctors trained to treat older adults. Lots of people don’t know that.) The way the editorial made the case, however, was deeply flawed.

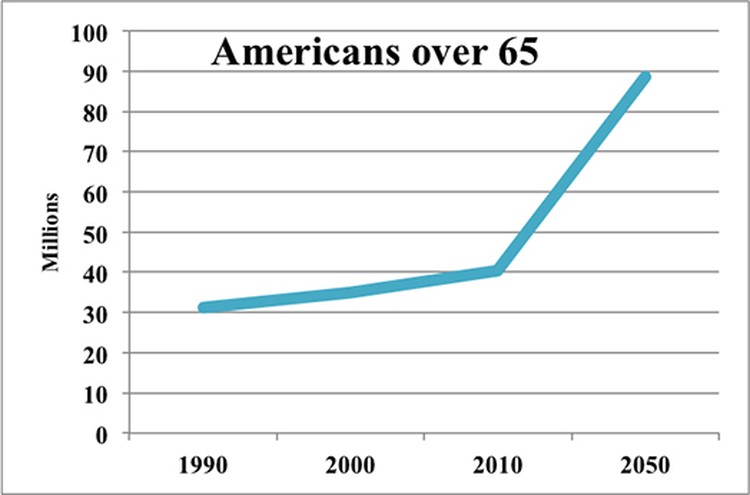

As Marcy Cottrell Houle pointed out in “An Aging Population, Without the Doctors to Match,” people under the care of a geriatrician enjoy more years of independent living, function better socially and physically, are happier and spend less time in hospitals and nursing homes. In other words, geriatricians improve lives and save everyone money. Since people over 65 are the fastest-growing age group, their role is getting more important every year. Yet there are fewer than 8,000 geriatricians in the United States (which translates to about four per 10,000 people 75 years old and up). The number is dropping. The pipeline is tiny; although every American medical school requires students to do a full pediatrics rotation, only 10 percent require coursework or rotations in geriatrics.

Most people assume geriatrics is a depressing profession. Houle, a biologist and award-winning author, clearly does too. She frames the problem as one of treating “People who aren’t dying but who grow more frail. People who have significant health concerns. People who suddenly find themselves in need of care. People who are, by and large, miserable.”

Whoa! Sure, as we age we have more health concerns. That’s actually one of the things that make older patients so interesting to diagnose and treat. But it’s wrong to equate needing care with being miserable. Worse, it’s deeply ageist to describe the vast and varied landscape between perfect health and incapacity as what she calls “the land of pink bibs”—drooling, demented and drugged into immobility.

It’s also a lousy way to recruit doctors or to change policy. Geriatrics requires several years of specialized training; how about debt forgiveness for medical students who choose it? Geriatrics is a time-consuming and low-paying specialty; how about improving the lousy Medicare reimbursement rates that make it hard to keep practices and clinics open?

Along with other surveys, a 2009 UC Davis study of more than 6,500 physicians showed geriatricians reporting the highest job satisfaction (and the happiest geriatricians have lots of patients over 75 and accept Medicare); how about promoting that consistent finding, along with the reasons behind it? Like internal medicine, geriatrics is a holistic practice that appeals to people who like to address a patient’s psychological, physical and social needs. Older patients are often fascinating and gratifying to work with. Let’s get the message out: personally and professionally, geriatrics is a deeply satisfying profession.

Above all, let’s confront the pervasive ageism that makes that fact so hard to believe. When late life, with its enormous variety and many pleasures, is depicted as “the land of pink bibs,” no wonder med students steer clear! When he went into the field, Samir Sinha, MD, was told he was wasting his talent. Now director of geriatrics at Toronto’s Mount Sinai and University Health Network hospitals in Toronto, Sinha blames institutionalized ageism for the geriatrician shortage: “A culture that devalues the old places little value on those who work with them.”

Internalized ageism on the part of society at large perpetuates this prejudice. God forbid that anyone find out you’re in the care of a geriatrician! Age denial seals the regrettable deal. Consulting a geriatrician, as Atul Gawande, MD, wrote in Being Mortal, “requires each of us to contemplate the unfixables in our life, the decline we will unavoidably face, in order to make the small changes necessary to reshape it. When the prevailing fantasy is that we can be ageless, the geriatrician’s uncomfortable demand is that we accept we are not.”

As it stands, within a decade or two, geriatricians will have to serve as educators and consultants for the physicians who are actually treating older patients. Imagine you had cancer, suggests Christopher Langston, who analyzes data on graduate medical education each year for the Hartford Foundation. “Would you be happy if your primary care physician consulted with an oncologist, but you never actually got to see one? That’s pretty much the situation we’re facing.”

The alternative is to change our attitudes towards age and aging, in order to change the culture. It’s a big step, and a necessary one.