Poor Roz Chast unburdened herself of her dislike of her mother and her pity for her father by describing their slow decline and dying, and doing it in the most public possible way, in a graphic narrative called Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir (2014).

Having burdened herself with guilt by lampooning her frightening, controlling mother, she partly atoned at the end by a series of moving portraits of her, done “from the life” right after her death. The fact that she explored her negative feelings before hinting that she had reached peace with her difficult mother may be what won the author her National Book nomination. I know people who closed the book before they got to the end.

In any case, Chast seemed to have laid her mother to rest.

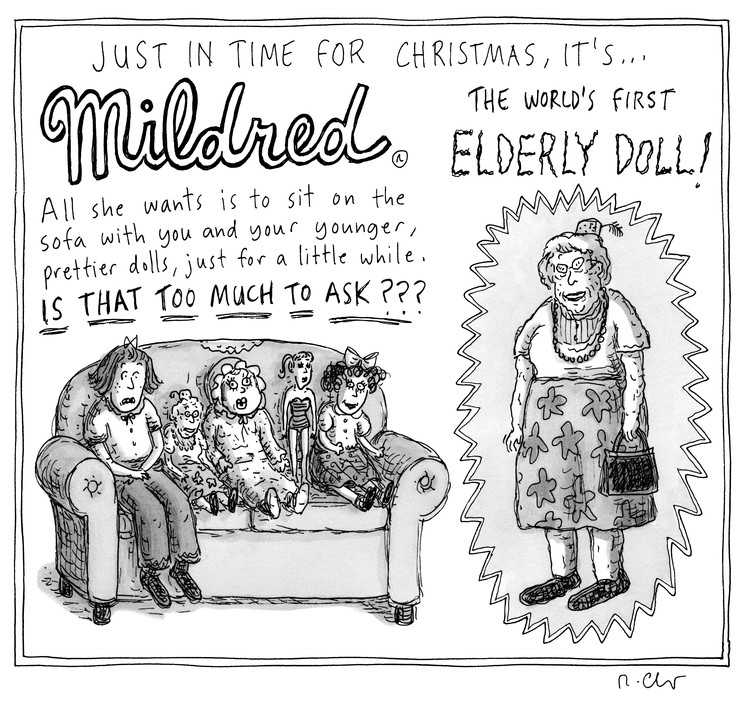

Whence, then, her cartoon, published in the New Yorker in December 2014, that ridicules the needy, desperate “Elderly Doll” in our society?

Dolls for little girls serve as babies or self-images. The American Girl doll, immensely popular, does both these things for my 9-year-old granddaughter. She was given this expensive doll, which has her hair color and type of hair, after her baby sister was born. She dresses it up, brushes its hair, makes its bed, collects miniature items for its decor.

Dolls exist to be cared for and passively manipulated. Children put words in their mouths in role-playing. Dolls, for obvious reasons, must be littler than—and can thus never appear to be much older than—the children who care for them. (In the cartoon, Mildred is no precious girl-doll but looks to the dismayed child who is forced to sit beside her like an “actual” old woman, much bigger than the child, with old-fashioned clothes and a humble stance.) Small children can’t imagine being much bigger/older. For such reasons, no one will ever design an Elderly Doll except as a witch. The “old hag” figurine comes in many commodified versions and, as a mask, is worn on Halloween.

This brief introduction to child development via doll therapy implies why it is “Totally Impossible!” (as a Roz Chast character would shout) for the girl-child to respond positively to the Elderly Doll’s pitiful request to just sit briefly with the younger, prettier dolls.

But in a cartoon it is embarrassing or insulting that an old woman is made to beg for this.

Pathos is what passes, in Chastworld, for sympathy, as her portrayal of her brow-beaten but impervious father showed. (How could he have loved and stayed with that monstrous mother, his wife?)

But being pathetic is not the way we grandmothers in the audience want to be seen. We are legion, we pretty women (and men) with grandchildren; and if the children are amiable, we do sit prettily and play with them. But Chast has no access to this world view. Through imagining Mildred, a stodgy, elderly, female doll, being rejected by a child whom she might well want to be loved by, Chast punishes her mother again.

Or perhaps, at an even less conscious level, herself? Not only out of remorse for writing a book that revealed both her parents’ decline in detail and implied that every daughter feels such end-of-life responsibilities as a burden, but also for growing older and becoming, as she might feel, stodgy and unloved herself? The cartoon form is a mighty vehicle for social commentary mingled with personal feeling. It can go deep as well as wide.

Now, why did New Yorker editors find this one humorous? Would they have published it had Chast drawn an African-American doll, with the hectoring voice saying, “All she wants is to sit for a little while next to the prettier, whiter dolls. IS THAT TOO MUCH TO ASK?” Or what if Chast had drawn a doll with Eleanor Roosevelt’s serene face and majestic posture? Are they so far from imagining themselves as grandmothers that they didn’t ask what real Elderly Dolls would think, looking at this humiliating projection?

© 2015 Margaret Morganroth Gullette

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.