The lines used to be drawn more sharply for me when it came to assisted suicide, now more often called “aid in dying.” After all, I had in-the-trenches experience. My mother was a charter member of the Hemlock Society, the first national right-to-die organization. (It has since merged with Compassion & Choices, which works to “expand choice at the end of life,” and to which I’ve belonged for decades.) She did eventually commit suicide, a decision I’ll probably never fully come to terms with, but which I respect. Because she was unwaveringly clear, so is my conscience. I’ve promised my children I won’t follow their grandmother’s example. But I too hope to control the circumstances under which I die.

I’ve made out a living will, designated a health care proxy, and talked them both over with my family and my doctor. That conversation is crucial, because if we’re too squeamish to talk about our own end-of-life priorities, we can’t expect more of the medical establishment. My partner’s health care proxy is his son, because he thinks I’ll pull the plug the minute he stops being entertaining. Mine is my sister, because it’ll be easier for her to pull the plug and I think that’s what I’ll want when the time comes.

Brooke Hopkins signed all the papers too. The lines seemed clearly drawn to his wife, bioethicist Peggy Battin, an internationally respected champion of end-of-life choices and author of seven books about how we die. Then Brooke broke his neck in a bike accident, and by the time Peggy reached the hospital he was enmeshed in the life-support systems that his paperwork was designed to avert—and paralyzed from the shoulders down. After the accident, Brooke opted again and again for procedures that kept him alive. At times Peggy had to make decisions for him, at which point things would get even more complicated. “Alongside her physically ravaged husband, she [watched] lofty ideas be trumped by reality—and [discovered] just how messy, raw and muddled the end of life can be,” as a moving profile in the New York Times Magazine described.

The bull looks different. (That’s my paraphrase of the mantra of Johns Hopkins bioethicist Thomas Finucane: “The appearance of the bull changes when you enter the ring.”) The matador’s point of view is different from the spectator’s. We can never know what another person is experiencing and tend to grossly underestimate the quality of life of people with disabilities. This mind-set is everywhere: in casual mutterings of “put me out of my misery if I ever get like that,” and casual conversations among healthy, middle-aged people about whether suicide after 60 is the rational alternative to “becoming a burden.” The Times article’s only mention of social class was to point out that this white, professional couple with good health care hoped to be able to continue to afford the astronomical costs of keeping Brooke healthy. They were fortunate and they knew it.

It’s not a particularly radical leap to conceive of assisted suicide and euthanasia as forms of discrimination against the old, the ill, the disabled and those who are no longer economically productive. That’s why the splendidly named Not Dead Yet came into being. This grassroots organization demands the equal protection of the law for the targets of so called “mercy killing” whose lives are seen as worthless. Activist Simi Linton, in My Body Politic: A Memoir (2007), describes some of the group’s members at a 1997 protest in front of the Supreme Court:

The shouters were saying, in effect, my life is worth living. That incontinence, respirator dependency, twenty-four-hour attendant care, pain, paralysis, blindness, and other conditions often depicted as tragic and intolerable don’t determine a wish to die. It is, more often, institutionalization, guilt about being a burden to others, fear of being alone and debilitated, poverty, inadequate medical coverage—all these things that lead to depression and a sense of hopelessness.

Once I wouldn’t have believed that, but now I do. Some come to the understanding after the fact, many in the moment of crisis. A friend’s 83-year-old mother-in-law was very clear about wanting no extreme measures if her heart failed. Then the bull looked different. She was too weak for a triple bypass, so surgeons installed two stents during a highly risky, seven-hour surgery—an extreme measure by any definition. Two weeks later she fired the visiting nurses and went back to playing the violin in her string quartet.

There is no basis to the idea that older people benefit less from medical treatment, including serious interventions like CPR, organ transplants, chemotherapy and dialysis. Much discussion centers on the high cost of these interventions, but undertreatment, which is rarely even mentioned, needs to be on the table as well. The criteria for medical procedures, to quote bioethicist Felicia Ackerman, should be the “desire to stay alive, medical need, and a reasonable chance that the procedure will work.” That’s it.

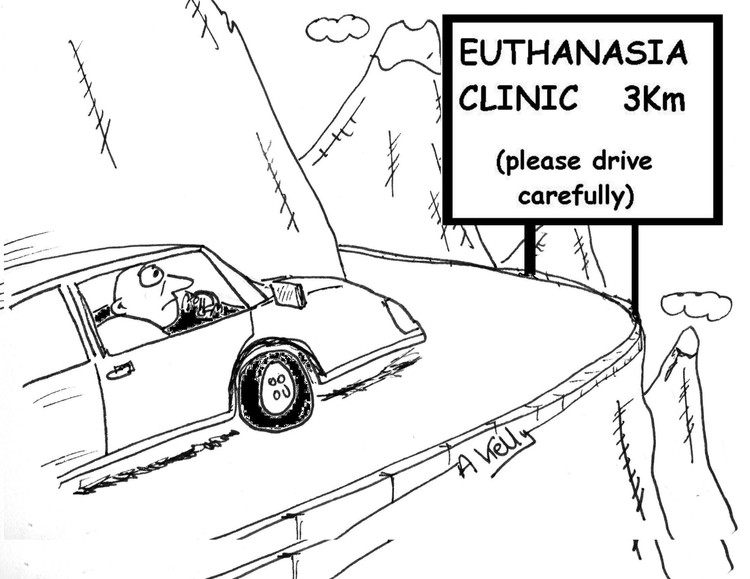

Ackerman said that during a conversation with age scholar Margaret Gullette, who warns about the slippery slope between “right to die” and “duty to die” in Agewise: Fighting the New Ageism in America (2011). Like disability rights activists, Gullette suggests that “suicide is a possible cultural outcome of believing that the state, your health-care system, your doctors, and possibly your children find you a burden.”

In the future, will the right to simply stay alive become less self-evident? Will olders increasingly be expected to justify the fact that they consume a disproportionate amount of government spending? Will that become an ever-taller order in a cutthroat, capitalist culture grappling with its own decline?

Peggy Battin didn’t buy this dystopian vision. A study she conducted in 2007 was one of the first to look empirically at whether people in Oregon and the Netherlands, where assisted suicide is legal, were being coerced into choosing to end their lives. She and her colleagues discovered “not the influence of a greedy relative or a cost-conscious state that wants you to die, but pressure from a much-loved spouse or partner who wants you to live. The very presence of these loved ones undercuts the notion of true autonomy.”

This is why those difficult conversations with the family and friends are so important. In the end, they matter more than any piece of paper. If I’m the health care proxy, I plan to pay close attention to my friend’s wishes and fears about medical treatment and to discuss them in the largest possible context: what life and death mean for her. If she wants extreme measures, I’ll have to overcome any bias and be her advocate; the life force is strong. Likewise, if she’s clearly ready to say good-bye, and even if I am not, I’ll have to speak up against intervention.

If I’m the one who’s dying, I’ll hope for such an advocate. Also for clarity—and luck. A few years ago the choices seemed clearer, but even then I had the sense to write, “Despite my professed certainties, all I know for certain is that I won’t know until I get there.” Age will have little to do with what I want, and nothing to do with what I deserve.