When I was young, I used to be so anxious about what to wear that, in the morning or before a party, my room would be strewn with discarded outfits. The mess outside exposed the mess inside—how inadequate I felt, how competitive, how miserable that I wasn’t pretty enough or rich enough to meet the day ahead. And often I was wrongly got up—overdressed, mainly. With too much eyeliner. Even when my appearance turned out to be appropriate for the occasion, I felt uncertain. I rechecked my look frequently. I adjusted my neckline, I marveled at my cleavage, I quick-peeked in mirrors. Distracted, sometimes I made myself the object of my attention rather than the people I was with.

And now? Quite the other way. I look forward to choosing clothes. Sometimes for pleasure I even take a minute before I go to bed to imagine what separates to put together for the next day, and I look forward to getting up in the morning. While I relish patterns, fabrics, shapes and colors, dressing goes fast. Once clothed, I check the mirror and then don’t think about it anymore. At 70, I have for some decades felt free, not of what is sometimes wrongly called vanity–I still want to look good and be visible–but of anxiety. Distinctly different feelings. Whether I succeed is a story others might want to weigh in on. But I feel I look good enough to be seen.

Why? How? What happened over my lifetime? To know one’s style is not a given once and for all—at 17, 35 or 75. We are not mannequins, forever the same hanger on which any current suit can be hung.

Over time, some life events and choices helped me change. After having been a skinny girl and after bearing a child at 27, I gained seven pounds. It wasn’t only a question of going from a junior size 5 to a size 8, but of rethinking my self-presentation. I had, by then, adjusted to having breasts. I was a teaching fellow and my main aim was to look older than my students, to get respect.

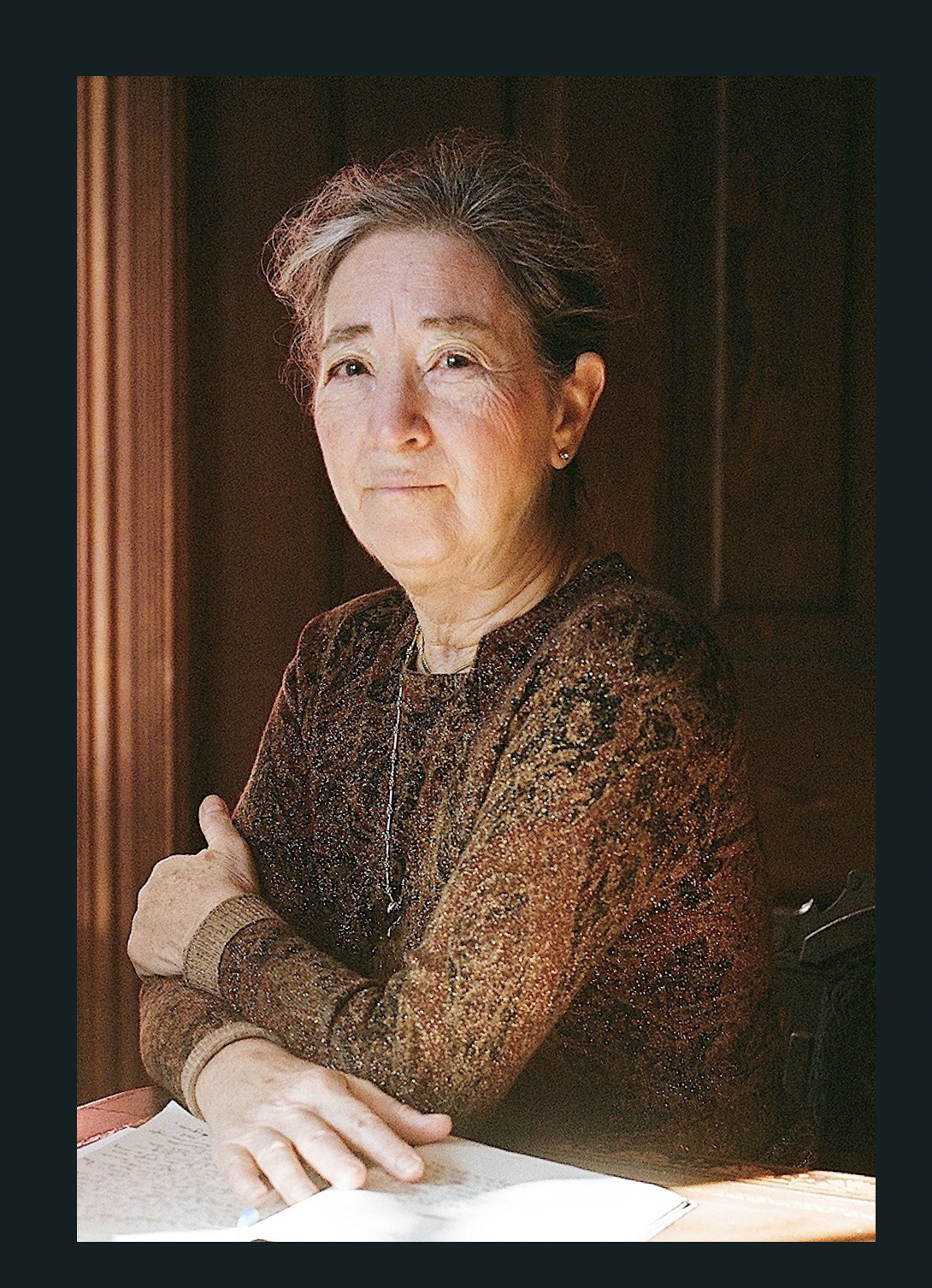

When I changed careers and became a university administrator, I redid my look again into menswear wool jackets over jewel-neck sweaters. I now had confidence that whatever I put on would do. More recently, as a writer and lecturer, I changed again. I gave up business wear for sweaters knitted by indigenous women, paired with well-tailored pants. To find one’s own look, and then to keep modifying it over the years, are gifts of aging—or, more exactly, what may come with aging through our one and only life course.

I have a friend about my age who dresses beautifully in classic clothing and always wears one small, exceptional piece of designer jewelry in silver. She has flawlessly cut, chin-level, white hair. When I complimented her on her look, the long discussion that followed led back inexorably to her having been sexually abused as a child. She used to want to be invisible. “It’s a strategy for protecting yourself from abuse,” she said soberly.

Aging helped her. She married a loving man who liked to buy her jewelry. She raised children; she found relief doing scholarly work. Her much-older abuser died. And now, widowed, “I’m not out there to attract people. So now I can wear what I want. I feel better about the way I look. What a relief.”

Telling stories of their idiosyncratic and changing relationships to dress may make sense to my age peers. Many a woman might be able to recount what led to her own current fashion amalgam. Doing this specialized age autobiography—in casual conversation or perhaps through photographs—can be both fascinating and worthwhile.

Being more centered, developing more self-confidence, can translate into a new relationship to the appearance you present to the world. It can go anywhere from an utter disregard for style (which is itself a way of self-presentation) to finding your own look. Style may be healing for some people.

In crowds, I keep on the watch for style; I see many women 15 years younger and 15 years older who capture my attention. We appreciate one another. As we grew older, some learned how to put together a look right for themselves. The women whose appearance I notice rarely choose the trends of this season or any season, but an amalgam of what is available and what they have decided is right for them. Each has her own way of relating to clothes. The so-called rules (no horizontal stripes, the highest heels possible) may be briefly useful to younger women. But as we age past youth, we each make our own rules.

One welcome side effect of finding our styles is that the bodies we used to fret and nag ourselves about now look better in our eyes. Once, earlier in life, our bodies had to be perfect; they inevitably failed to be. At a certain age, perfection seems like a preposterous ideal for anyone because we have discovered the sources of that phony ideal. The fashion magazines with their photoshopped beauties. The plastic surgeons now trying to trap our daughters. The patriarchy willing us to be anxious objects. And knowing all this, we criticize these sources rather than our bodies.

Many women way past youth—not fashion plates but tasteful dressers and extraordinary individualists—are fashionable in fresh senses of the word that make the word itself seem stodgy, consumerist and old-fashioned. The women I observe seem comfortable in their clothes. Comfort is an important value that needn’t quarrel with esthetics. Some women put pieces together in fascinating ways. (Frenchwomen alone used to be praised for this.) Having style, they don’t have to be conventionally beautiful or slender or wear the latest. They make a statement about who they are. Challenging the stereotypes of older women as drab, unappealing or worse, they are satisfied with the way they have decided to be visible.

Is there any doubt that women can be stylish while no longer being young? Editors! Photographers! Younger women! If you aren’t looking at us, why not? Seeing is a cultural practice, so go ahead and practice more.

Margaret Gullette expands on the theory behind this blog in a chapter called “The Other End of the Fashion Cycle” in her prize-winning book Declining to Decline: Cultural Combat and the Politics of the Midlife.

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.