Sally Jacobson had about a month to live.

A few months before, she’d been tired, sure—not feeling so great. But she was bustling along, balancing work and family in Grand Forks, ND. Then she got some great news: a promotion at work.

Within a week, her health had deteriorated so much that she couldn’t walk and breathe at the same time.

The diagnosis was autoimmune hepatitis, a disease of undetermined cause that made her body attack her liver as if it were an infection that needed to be destroyed.

She ended up in a wheelchair, with her husband as her caregiver. She couldn’t get out of bed by herself—couldn’t get off the toilet by herself. And every two to three days, she underwent thoracentesis, a process that involves having a needle stuck in your chest to remove fluid buildup.

On March 31, 2006, at 61 years of age, Jacobson was placed on the waiting list for a liver transplant. “And that’s when the surgeon asked if I would accept an older liver,” she recalls of her Mayo Clinic doctor. “He said, ‘It might give you 15 years.’ And when you know you don’t even have a month left to live, that 15 years is a pretty awesome gift.”

Many older people believe they can’t donate because their organs are worn out. Mostly, they’re wrong.

Three-and-a-half weeks later, Jacobson received her liver—from a man who died at 82.

Today, Jacobson is doing well. In fact, her doctor now believes that her liver will last past those initially predicted 15 years, she says. She spends her days volunteering at an impressive pace, spreading the word about the desperate need for more organ donors—especially the fact that, despite what too many people believe, you’re never too old to be a donor.

Why Older People Don’t Sign Up as Often to Be Donors

These days, registering to be an organ donor can be accomplished at as mundane a place as the Department of Motor Vehicles. But when today’s older generations were in their formative years, the idea of donating an organ was a profound one.

The year 1954 marked the first time an organ was successfully transplanted. It was a kidney from a living donor. In the 1960s, organ transplants from deceased donors began—and made a media splash. The surgery was featured on magazine covers and in headlines.

“Some time ago, organ failure meant certain death,” pioneering transplant surgeon George M. Abouna later reflected. “With the advent of transplantation came the hope of a second chance of life.”

During the early years, organs were generally only transplanted from younger people. It was in part because of Abouna’s work that doctors gradually learned that organs from people over 60 could work well too.

Nowadays, organs from older people are transplanted all the time, usually to people who are of a somewhat similar age. Still, members of older generations are less likely than those of younger ones to register to be organ donors.

According to a 2012 Gallup survey of more than 3,200 people, 66 percent of Americans ages 18 to 34 have granted permission on their driver’s license, and 52 percent of people 66 and older have done so.

Sixty-six percent of people on the waiting list for a transplant are 50 and older—prime candidates for an organ of about the same age.

This lesser willingness among older people matters because every donor matters. For one thing, not everyone who registers to be a donor can become one in the end—no matter their age and health.

“You need to die in a hospital to be considered an organ donor, and the majority of people do not,” says David Klassen, MD, chief medical officer of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). “Most die at home or in some other place.”

You also must die in a manner that preserves organ function—usually from an event that causes brain death, such as trauma or a severe stroke.

But older donors in particular matter because “the most rapidly growing subgroup of the waiting list is older adults,” says Dorry Segev, MD, a transplant surgeon and associate vice chair for research at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “A 70-year-old waiting for a kidney doesn’t need kidneys from a 20-year-old. They could benefit significantly from kidneys from a 70-year-old.”

The problem isn’t that older people don’t believe in organ donation. Over 90 percent do, according to the Gallup survey, which was conducted for the US Department of Health and Human Services.

The first reason they say they’re not signing up is they think they’re too old—that their organs are worn out and undesirable, says Kimberly Downing, PhD, a social behavioral researcher who’s been studying donor registration among older adults for 10 years.

But that’s just the surface answer. Probe deeper, and you find that the reasons are also health related. Because of a chronic illness, disease or medication, they’ve decided, “I’m not good for anybody,” says Downing, who’s the codirector of the Institute for Policy Research at the University of Cincinnati.

Experts say they’re often wrong—and it’s costing lives.

Why Older Organ Donors Are Desperately Needed

If today is an average day, 22 people will die waiting for an organ transplant.

This minute, over 122,000 people are on the waitlist. Almost 80,000 of them are medically eligible to receive an organ right now. Yet only 29,532 organ transplants were performed in 2014.

The necessary organs just aren’t available. The number of donors has been pretty stagnant for over a decade, yet the number of people on the waiting list has kept right on growing. (In 2005, there were just 90,526 people on it.)

And 66 percent of people on the waiting list are 50 and older, according to UNOS, the nonprofit organization that manages the United States organ transplant system. These are prime candidates for similarly aged organs.

How Health and Age Affect Organ Donation

Both your age and your health can affect what you’re able to donate—but not to the extent many people think.

Health-wise, what affects one organ doesn’t necessarily affect them all. “If you die of heart failure, you’re not likely to be eligible as a heart donor, but you might still be acceptable as a liver donor, for instance,” explains Klassen, who was a transplant nephrologist for 28 years at the University of Maryland before he joined UNOS in 2014. “Or a person who has had diabetes for many years might have suboptimal kidney function and therefore not be really a good kidney donor but might be a liver donor.”

Even if you’ve had cancer or have been told you can’t donate blood, that may not preclude you from being a donor.

Age has a similar sometimes/sometimes-not effect.

When David Coffee’s mother, Christine, died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage in May 2015, he was promptly told that she’d make a great liver donor. “I said, ‘You’re kidding me! A 90-year-old lady?’” he recalls. She was an active woman—healthy and vigorous—but still, “I was just surprised that they could use an organ from her at that age.” Her match was a 60-year-old man in New York.

Donated tendons help people move, donated veins prevent amputations and corneas help people see.

Coffee would soon learn that his mother had become the second oldest organ donor in the history of LifeGift, the organ procurement organization for north, southeast and west Texas, which was established in 1987.

The nation’s oldest donor was also a LifeGift donor: in 2006, Carlton Blackburn’s liver went to a 69-year-old a few days before Blackburn would have turned 93.

To transplant doctors, age really is just a number. “Seventy is the new ‘we’re not sure,’” says Segev.

That said, in general, organs are often matched up with people of similar ages. “One of the latest paradigm shifts in transplantation is to try to match the wear-and-tear of the organs with the wear-and-tear of the patient receiving them,” Segev says. “The phrase is, ‘to find organs that look like you.’”

“Typically, at least for kidney transplants, what we attempt to do is match organs that are expected to last the longest with patients who are expected to live the longest, or require them the longest,” says Klassen. “So we try to match the expected longest-lasting organs with, say, younger people.” But an organ that has a more limited, predicted lifespan can work well for someone who’s older. Klassen also notes that older people can sometimes be living donors—for example, donating a kidney to a family member.

How Organs Are Evaluated

Organs are medically evaluated before they’re transplanted. During her research, Downing has found that many older people don’t realize that—and therefore choose not to be donors. Women, especially, often fear they could actually harm a recipient through donation.

Depending on the organ—kidney, pancreas, liver, intestine, lung or heart—it may go through lab tests, physical tests, examinations or a biopsy, Segev says. Some organs can even undergo a bit of renovation before transplantation. “For example, kidneys, liver and lungs can go on perfusion machines,” he says. “Once you’ve taken the organ out of the patient, you can put it on a machine, and that machine can improve the function of the organ.”

But say it turns out none of the organs are usable after all. There are still many more things people can donate—namely tissues. For example, donated skin can help people with serious burns, reducing pain, scarring and infections. Donated bones can be used for spinal fusion and dental implants, or for filling in around knee or hip replacements—and even to replace bone that was lost to cancer. Donated tendons help people move, veins prevent amputations and corneas help people see.

At age 71, Robert Kauffman of Arizona died two weeks after he underwent elective surgery for a brain aneurysm. He’d been an athlete all his life, even playing NCAA basketball. “He was still playing singles tennis,” says his wife, Betsy Kauffman, who volunteers to tell her story through her state’s organ procurement organization, the Donor Network of Arizona. “He was very active physically.”

After some of his tissue was donated, Betsy Kauffman received a letter from a recipient’s family to thank her. “It turned out their daughter was trying to be in the 2016 Olympics and tore her ACL,” Kauffman says, referring to a serious knee injury. “So we were able to fix that. How cool is that?”

Other Factors That Keep People from Donating

Though concerns about age and health are the main reasons older people cite for not becoming organ and tissue donors, some other factors do come into play.

For one thing, organ transplantation is relatively new. It made the news in the ’60s, but it wasn’t until the1980s that it started becoming more common, thanks to the newly discovered immunosuppressant cyclosporine, which helped prevent people’s bodies from rejecting the organs. Because older generations didn’t grow up knowing anyone who had a transplant or who was a donor, they’re dealing with a learning curve, Downing says.

Jacobson, who had the liver transplant in 2006 at age 61, experienced some of that learning curve—mostly through relatives. “My mom had a hard time understanding it,” she says. “She’d introduce me to people, ‘This is my daughter, Sally. She had implants.’”

Another factor that affects older people more than younger ones is concern about how the donation may impact their family, Downing says. One thing they worry about is cost. They needn’t worry, though. Donation costs donor families nothing.

As far as emotional impact goes, organ donation can actually be a source of comfort. In fact, 83 percent of people believe it helps families cope with their grief, according to the Gallup survey.

Coffee, whose mother donated her liver at age 90, can testify to that. “There’s the comfort of knowing that even in that sad situation, good is coming out of it,” he says. “And then also it’s that little bit of immortality—to say, oh my gosh, she’s still living on—and it’s kind of amazing.”

It is a good idea, however, for people to talk to their family about their decision to become a donor, because if the family were to object at the hospital, their wishes would likely be respected. “Organ procurement organizations do pay very close attention to family wishes,” Klassen says. Though a family’s distressed pleas could legally be ignored, it would be unusual for the organization to go against significant family objections.

How to Register as an Organ Donor

In the United States, organ donation is completely humanitarian. Buying and selling organs is illegal, and organ procurement is highly regulated by a number of federal agencies. (It’s also overseen by UNOS and carried out according to state laws.)

So each person on that transplant waiting list is dependent on the charity of their fellow human beings. Signing up to be a donor, therefore, is a profound, potentially lifesaving thing to do. Yet it’s very easy. You can register online or when you renew your driver’s license at the Department of Motor Vehicles.

In 2012, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched the 50+ campaign—complete with a video, brochures and public service announcements—to urge people 50 and older to register as organ donors. More information about donating organs as an older adult, including downloadable materials, is available through that campaign here.

Jacobson, whose liver turned 91 this year, is grateful for the time her donor has given her. She and her husband have now been married 52 years, and since her transplant, they’ve welcomed three new grandchildren into the world.

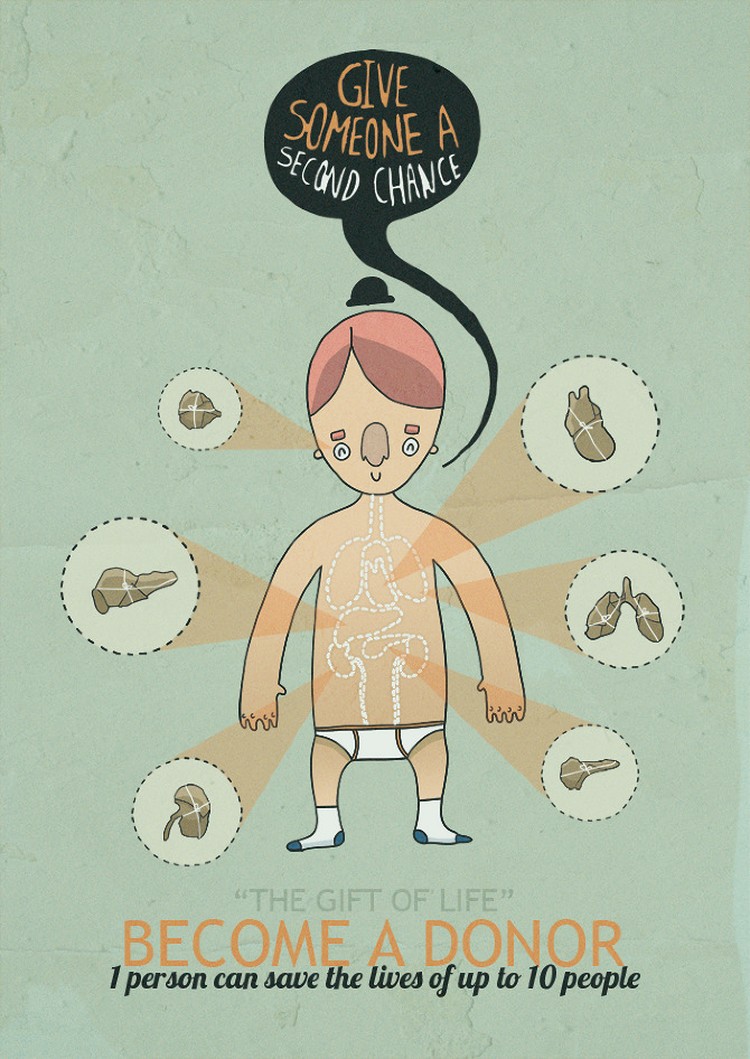

Jacobson volunteers tirelessly with LifeSource to spread the word about organ donation. “I believe in paying it forward,” she says, “because I’ve received the most awesome gift of all—the gift of life.”

Leigh Ann Hubbard is a professional freelance journalist who specializes in health, aging, the American South and Alaska. Prior to her full-time freelance career, Leigh Ann worked at CNN and served as managing editor for a national health magazine. A proud aunt, Leigh Ann splits her time between Mississippi and Alaska.