When I flew to Montreal for a college reunion, senior discounts helped me pay for my airfare and hotel room. While I was happy to take advantage of these perks of my years, was I more deserving of such modest concessions than, say, a 20-something on the same plane?

I thought about that after I came across a heated debate online about senior discounts, an argument that erupted in comments responding to a blog at Priceonomics.com. This dispute pitted resentful millennials in their 20s and 30s against indignant boomers. The millennials resented the fact that their generation, frequently unemployed or underemployed, received no age-related price breaks while many boomers—who had wrecked the economy, they said—got discounts just because they were older. Some of the boomers, in turn, dismissed some of the millennials as “whiners.”

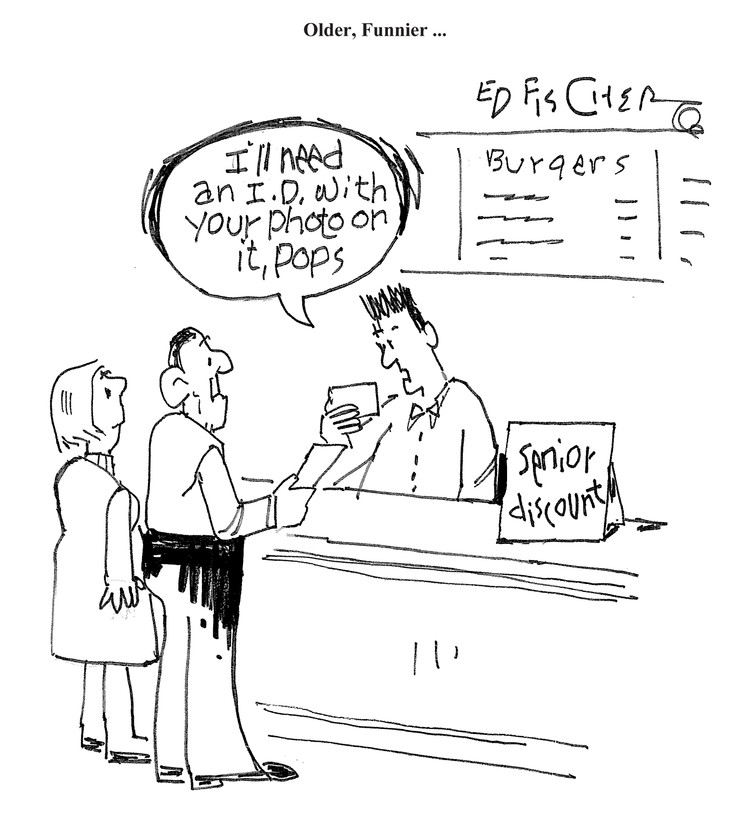

Further research turned up a column that ran in USA Today, headed “Why we should kill senior discounts.” Former Washington journalist Don Campbell, a member of the newspaper’s board of contributors, argued that the discounts fuel “the growing economic divide between struggling younger generations and a self-obsessed, mostly well-to-do, older generation.” He wondered why “senior citizens—the most pampered, patronized and pandered-to group in America—get to save money simply by maintaining a pulse.”

That got my dander up. The millennials and Campbell based their objections on wrong assumptions. First of all, older people are not “mostly well-to-do.” The Great Recession hit many of us hard. Today, almost half of older Americans are economically vulnerable and have incomes that are dangerously low, according to a June 2013 report by the Economic Policy Institute. In other words, those seniors are close enough to poverty that a serious medical problem could push them over the edge. Many younger people seem to assume that elders have no medical expenses because of Medicare, but the Employee Benefit Research Institute found that Medicare only picks up the tab for about 60 percent of those expenses. What’s more, that 60 percent doesn’t include the staggering cost of long term care.

My second point: most senior discounts are offered by businesses with their own bottom lines in mind. They know that people living on fixed incomes are often reluctant to spend and that selling to them for less is better than not selling to them at all. Sometimes the discount is designed to take up slack in off-hours. If a restaurant is practically empty in late afternoon, why not fill it with older people who don’t mind eating early when it’s a bargain? That kind of markdown may be one-part compassion and respect for elders but it’s two-parts hardheaded business sense.

Occasionally, critics reject senior discounts on the grounds that they bolster the stereotype of doddering ancients who need all the help they can get; in other words, the discounts themselves are seen as a form of ageism. But I suspect it’s the other way around, and ageism—prejudice against older people—is what leads to complaints about the discounts. All kinds of price breaks are available these days for anyone willing to do a little digging. Businesses routinely lower their prices for children, students, veterans, loyal shoppers, early birds, frequent flyers and safe drivers, among others. They court AAA members as well as those who have joined AARP. Why do the complainers focus only on seniors?

Elders aren’t an exclusive group. Those who aren’t yet eligible for senior discounts are older-people-in-waiting, and that includes my 2-year-old granddaughter. Fixed incomes and discounts will be everybody’s, someday.

As for me, I’m planning to go right on asking for my senior discount for as long as I can maintain a pulse.

Flora Davis has written scores of magazine articles and is the author of five nonfiction books, including the award-winning Moving the Mountain: The Women’s Movement in America Since 1960 (1991, 1999). She currently lives in a retirement community and continues to work as a writer.