I recently picked up Katie Hafner’s Mother Daughter Me: A Memoir (2013). All it took was a glance at the book jacket for me to know that the author was telling part of my story along with her own.

Like Hafner, I’m a widow in my 50s with a teenage daughter (actually, two). Like me, Hafner is a dutiful daughter with a conflicted relationship to an alcoholic mother. Hafner’s mother stopped drinking on her own; mine enlisted the help of a support group.

What happens when our mothers move into our homes is where we diverge.

It was easy for me to relate to Hafner’s emotions. Her mother, Helen, independent at 77, was living in an unsustainable situation, and Hafner would not abandon her in her time of need. They decided to live together; they’d give it a year.

Hafner and teenage daughter, Zoë, had already had to regroup after Hafner’s husband (Zoë’s dad) died. They had moved forward, leaning on each other, and enjoyed an enviable mother-daughter bond. They both optimistically assumed that the move with Helen would be beneficial to all concerned. Wishful thinking, for certain—in less than six months, Helen and Zoë were barely on speaking terms.

Neither Hafner nor her often-estranged sister ever challenged their mother on their upbringing—the unmet needs, the instability or the ultimate abandonment as Helen forfeited custody when Hafner and her sister were 10 and 12 years old. Indeed, Helen lived most of her life ignorant of the truth of her daughters’ childhoods. It was not until living with Helen again as an adult that Hafner really addressed the root causes of her often-strained relationship with her mom.

It seems I had an easier time with my multigenerational household. I married later in life than Hafner and my husband and I bought a house that would accommodate my widowed mother when the time came. It came sooner than expected when, after a couple of fender benders, Mom gave up driving: she moved in when we did. Our property had a two-car garage that the previous owners converted to a charming cottage with an inspired floor plan that made the most of the small space. The cottage was a stand-alone building with its own address and utilities.

By the time I married, I had put my own alcoholism behind me, was living the examined life and was enjoying a harmonious relationship with my mother, even though we didn’t always see eye-to-eye. Having her next door in her last decade of life brought us closer. When my daughters were born, our living arrangement provided my mother with what she claimed were the happiest years of her life.

Now I am in the age bracket Hafner was in when she embarked on her experiment. I am also a woman who juggles work and the girls’ incredibly active school and extracurricular activities. We also circled the wagons when the girls’ dad died, and today we are a tight-knit, mutually supportive family of three. In reading this memoir, I wondered if, for my mother, I could compromise the safe haven I created for my daughters, as Hafner did. That we’ll never know, but I am glad I don’t have to make that choice.

Katie Hafner earns my admiration for what she did. I felt the same sense of obligation to my mother. I am in a position to understand and appreciate the potential risk and reward Hafner assumed. The three women didn’t escape unscathed, but enlightened and content to live apart. Despite knowing how their story ends, right up to the final page I rooted for their living experiment to work.

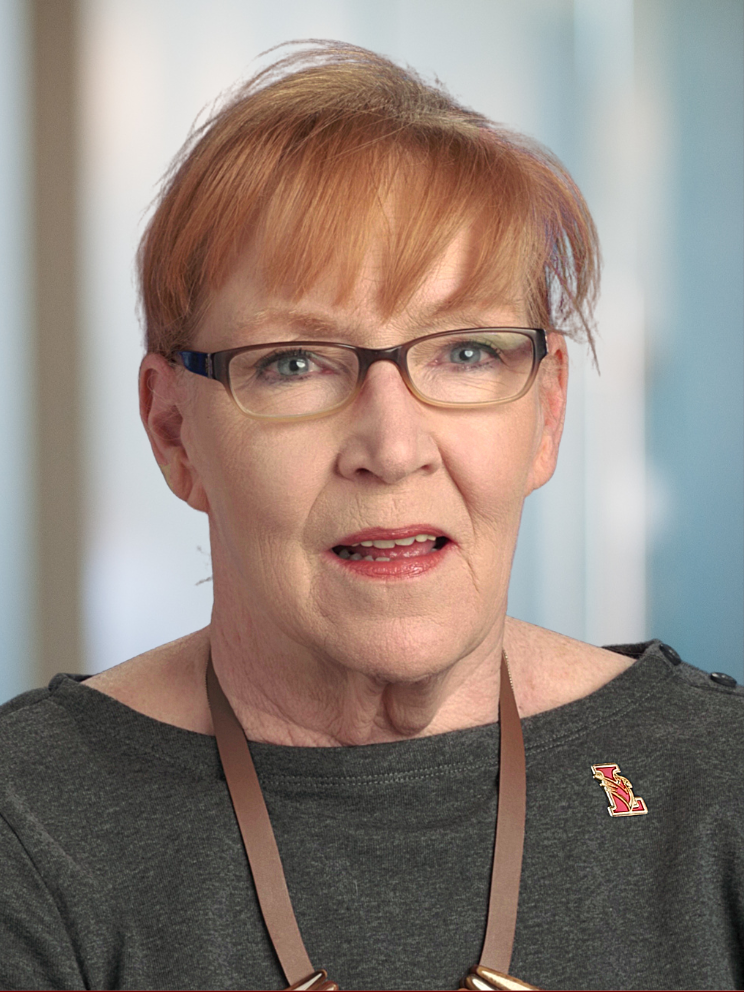

Pepper Evans works as an independent-living consultant, helping older adults age in place. She is the empty-nest mother of two adult daughters and has extensive personal and professional experience as a caregiver. She has worked as a researcher and editor for authors and filmmakers. She also puts her time and resources to use in the nonprofit sector and serves on the Board of Education in Lawrence Township, NJ.