Amid America’s turmoil and woe, I like to think of my mother and father.

I am 84. My mother died in 2010 and my father in 1974. Though they are long gone, I hear what they might say and know what they would do now, as if they were close by. They would be reassuring me and keeping up my spirits. They would be carrying signs at the rallies with all of us.

At demonstrations against the Trump administration, I see many people with gray and white hair. My cousin Annie says, “Our demographic is over-represented at these protests, and I couldn’t be prouder. Still marching after all these years.”

At the demonstrations, I see people as old as I am everywhere. At a “No Kings” demo in Waltham, they carried signs saying, “Save Social Security,” “If a Parade, then Medicaid” and every other kind of message. One 80-year-old friend carried a cowbell and a sign reading “Basta con el miedo!” (“Enough with the fear!”). Another sign read, “I am 90, with Parkinson’s, and I am pissed.” A woman in a wheelchair held a sign saying, “I am 83, my first protest!” A man a little younger than I, wearing an Army cap from the Vietnam era, told me, “I didn’t know then that people could object and protest. Now I know, and I do.”

Many of us have had a lot of practice: Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq. We protested every bad government action.

I learned nonviolent civil disobedience from my parents, growing up in Brooklyn. They were activists even before Vietnam. During the civil rights movement in 1964, driving through St. Augustine, FL, they attended a demonstration. When protesters refused to leave a sit-in attempting to integrate the Ponce de Leon Motor Lodge restaurant, some were arrested and jailed. My parents were not arrested, but they were present, in solidarity, as lifelong believers in human rights, in including Black Americans in the American Dream. What we now call DEI was already a good goal.

And me? Young as I was, my good-girl head was down, finishing my master’s thesis on Proust in graduate school far away. I was merely an educated girl, not political yet, not focused on the common good as they were.

Both of them had been radicals in the 1930s, when Jewish leftists and others hoped that a popular front could remake US labor relations, control capitalist greed and bring America closer to equality for women and people of color. Paul Robeson was one of their idols, along with Eleanor Roosevelt.

Later, they opposed the Vietnam War, just as my husband and I did. In 1968, running against feckless Hubert Humphrey, treacherous Richard Nixon promised to end the war and then prolonged it until more than 50,000 men my age died, as well as countless Vietnamese and Cambodians. In 1972, my father worked to elect Elizabeth Holtzman, also of Brooklyn, to Congress. So she was in the House of Representatives in time to vote to impeach the corrupt Nixon in the summer of 1974.

My father, with ALS sapping his body, had followed the investigation and trial avidly from the green couch in the living room. But he missed out on the ending. By August, he was in a coma; he died two days short of Nixon’s ignominious exit.

The night Nixon left, making his awkward, hypocritical peace signs, my mother and I were dining in the dim kitchen with my cousin Sherry, grieving and rejoicing. In that painful, complex mood, we poured some wine and drank to him: “Marty should have been here to see this day.” “Daddy should have been here.”

I know my parents would be out with me on the streets now. They were there, in a sense—at a #HandsOff rally on April 5 in Newton, at an April 19 event to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the beginning of the American Revolution in Waltham, and then at the “No Kings” rally.

The signs were clever and scathing at all these events; drivers going by were honking in approval, shouting, applauding. My laconic father’s sign would have said, very big, in block letters, “NO!” Once when my mother was in her 90s and had lost many memories, I asked her, “What is wisdom?” She answered unhesitatingly: “The greatest part of wisdom is kindness.” Her sign, which I saw an older woman hold at the Waltham rally, would have read “Make America kind again.”

“Nothing is stranger than the position of the dead among the living,” Virginia Woolf wrote in her first, unpublished novel, Melymbrosia. I find it marvelous that my parents can still stand by my side.

The rest of our family is in the streets too: our son and his children in New York City. That solidarity is so welcome to us—just as it must have been to my parents when we opposed the Vietnam War early on, when they felt alone and scorned, when so few Americans had yet come to their senses.

Intergenerational solidarity is precious. That preciousness includes not only the next generations but the oldest too. To all of us lucky enough to have older people in our lives, they comfort us by their presence. Repositories of family lore and legend, they dole out secrets and, for better or worse, guide us by their experiences. And sometimes by the energy of their activism, right now!

I see my parents’ faces vividly. I summon them and their will to do good, which survives them in this national emergency. Their memory is a blessing in the here and now and the strife to come.

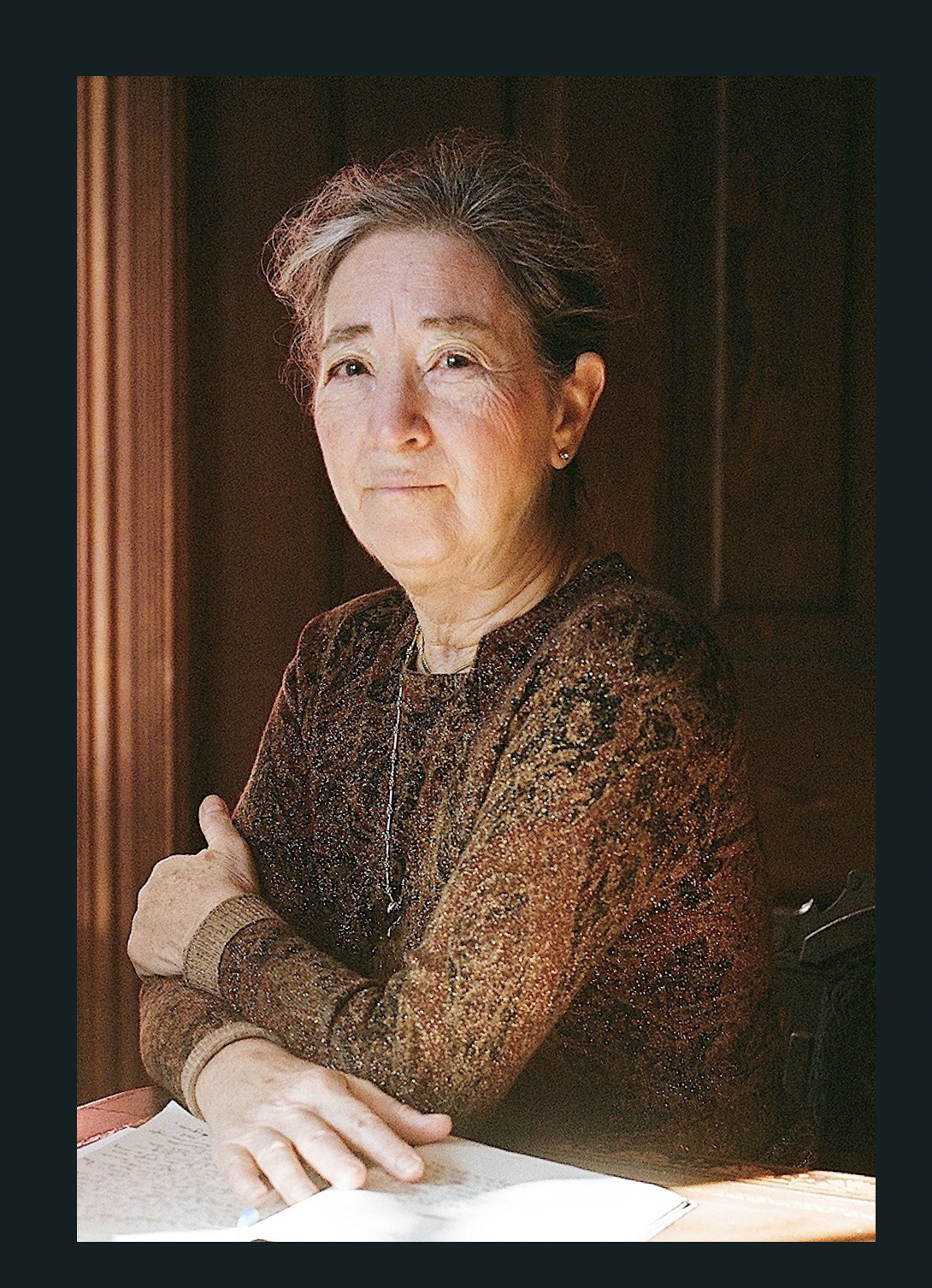

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.