The residents of nursing facilities in the United States died in disproportionate numbers from COVID, when they should have been protected by the Trump administration’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, the 50 states’ departments of health, and the owners and operators of their so-called “homes.” In 1,950 facilities where they were protected, they survived.

Instead, as my recent book American Eldercide shows, in the rest of the 15,400 facilities, the residents were locked in, four or more in a room, open to the infection of any one of their companions, left without masks or adequate attendance or, for many crucial months, state inspectors, who could have measured conditions such as understaffing and urged an anxious, preoccupied, devastated nation to pay attention. Many died unnecessarily and prematurely who could have been saved. In the panic of 2020-2021, many were not buried properly.

Since then, there have been no reproaches for the guilty, no memorials for those blameless, COVID dead, no separate commemorations. At this distance of silent years, can those special, 200,000 deaths be made to seem a vast communal loss, worthy of social as well as familial grief?

“Sweeping up the heart/ the morning after death” (Emily Dickinson’s charge to us) is no simple process when society prefers to forget the hardships of COVID and that marginalized and abandoned group who died.

In Oedipus at Colonus, the extraordinary play by Sophocles, the Athenian dramatist created suspense about whether the exiled old man will be buried as a polluted and feared outsider or with honorable commemoration. Sophocles wrote the final, and least-well-known play of his Oedipus trilogy shortly before he himself died at the age of 90. The play makes clear that a good end-of-life for Oedipus the King refers not to the end of his exile, not to his old age, nor to the manner of his dying but to what happens to his memory after he dies.

In the course of the play, Sophocles turns Oedipus from a miserable, self-blinded man, inadvertently guilty of parricide and incest, into a powerful protagonist with a just grievance. Oedipus successfully redescribes his ferocious, lifelong suffering as unjustified. The wrong done him by the gods can be assuaged only by proper recognition of his posthumous standing.

A good burial, rather than a good death, had been on Sophocles’ mind at least since he wrote the Antigone, a play that forcefully argued for the ethics (and human instinct, and religious necessity) of offering a posthumous ritual to a dead brother, even after he had been proscribed as an enemy of the state. The residents in nursing facilities in 2020 were not enemies of the state, yet many died alone, unable to breathe. No one could wish such deaths on their worst enemy.

Now, in old age, writing a play about a hapless old man who had been afflicted with wretchedness all his later life, Sophocles must have felt the desire for a righteous, state-sponsored, ritual pressing on him even more urgently.

He made Oedipus mournable. He rewrote the king’s life story to make Apollo declare that Oedipus was worthy of being buried in a special place, a sacred grove.

“There,” said he, “shalt thou round thy weary life, A blessing to the land wherein thou dwell’st, But to [any] land that cast thee forth, a curse.”

The resting place and the rites promised by the Athenian government will allow him to end his life as a benediction to the state that recognizes his memory as a blessing.

In the COVID Era, the Colonus is movingly relevant. Like so much in the classic literature of grief, the concept of a good death and the propriety of commemoration have a new resonance now. We need to attune ourselves. President Joe Biden started the healing process for the nation in two grand public ceremonies for all the US dead soon after his inauguration. Both times, he failed to take special notice of the residents of nursing facilities. Perhaps he thought healing divisions required him to ignore the failures of the previous Trump administration, responsible for abandoning them. In any case, no one learned the lessons taught by the nursing facility deaths.

That omission leaves us little imaginative choice but to think of the residents, most of whom were separated from their loved ones while they were dying, as pained and lonely, passive and bereft. As a result of the Eldercide, they may be judged to have had a miserable end, a “bad death.” It would be purblind and cruel to leave this judgment as the last word on the luckless group who found themselves in nursing facilities when COVID struck.

Remembering the dead residents appropriately is the next ritual the nation needs to offer the families and friends that grieve for them without closure. What would count as providing those 200,000 people with their own “sacred grove”?

James LoMastro, a member of the coalition I work with, DignityAllianceMA, which advocates for better conditions for residents of nursing facilities and options for never having to enter one, reminds us of a popular saying, that “We die twice: once when our body dies and once when our name is spoken for the last time.”

Let there be no such “last time” for these names. American Eldercide suggests that the national government sponsor a locus amoenus, a noble and pleasing monument in the nation’s capital, built out of repentance and grief, in which the names of all the residents who died of COVID would be listed. These would be living names. Every visitor would be able to click on a name and by so doing, see the individual’s photograph, read a tribute and leave with the intention to never again let public health fail so many.

The current Congress will never see age justice as an important goal for healing the nation. All of us who care for the old, the sick or people with disabilities, or who wish for a dignified old age for ourselves, may, however, believe that some honorable commemoration will come and will work to bring about that finer day.

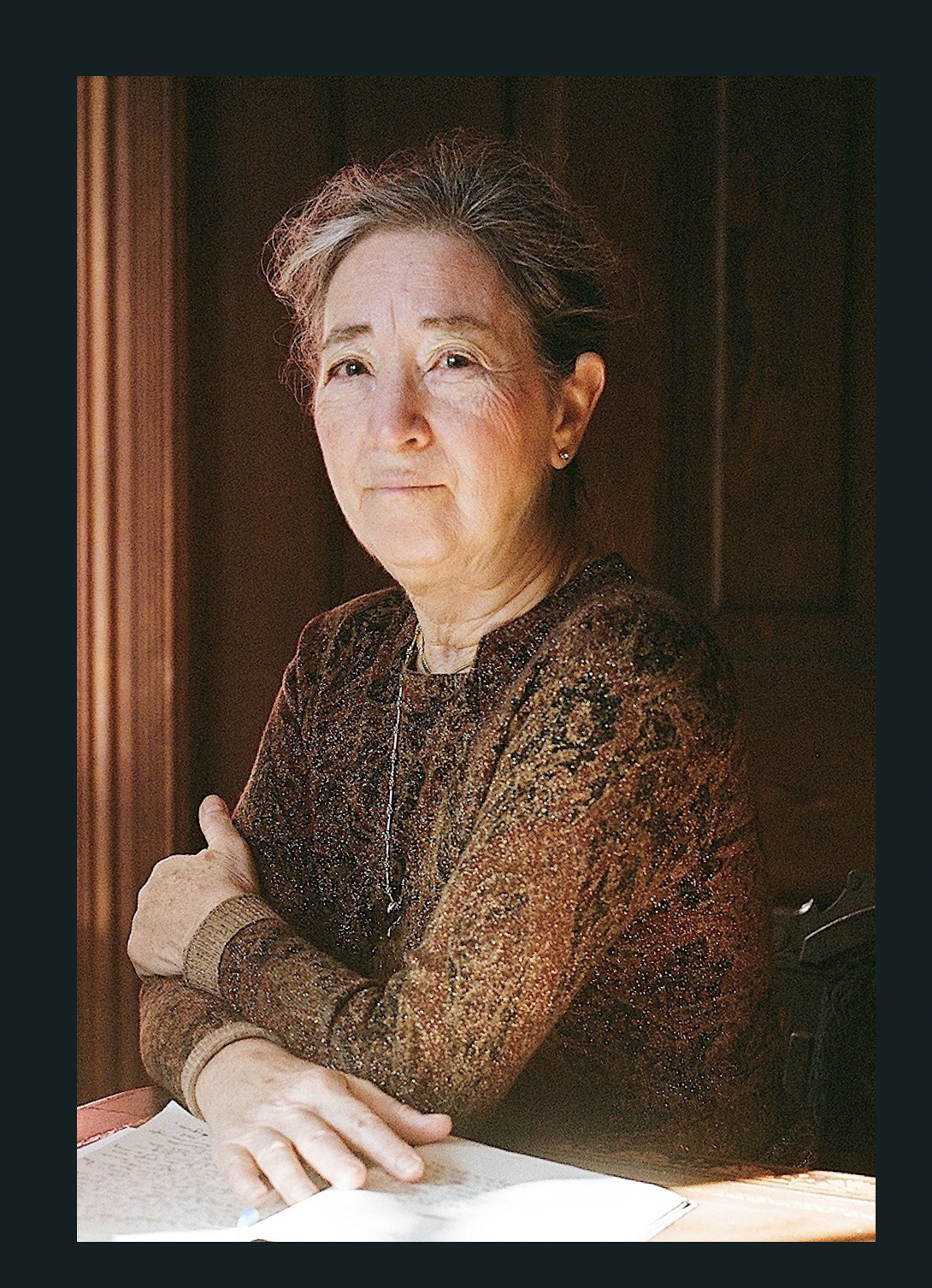

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.