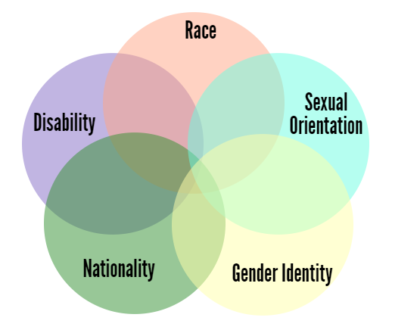

… What 2020 brought home for me was that being anti-ageist means supporting every movement for equal rights. It’s a big ask, but we cannot dismantle ageism without dismantling ableism, and racism, and sexism and all the rest, because these systems reinforce and depend on each other. (That’s intersectionality—a clunky word for an important concept developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw and other Black feminists.)

That’s why I’m delighted to announce the release of Ageist? Racist? Who, Me?, Old School’s free guide to starting a consciousness-raising group around the intersection of ageism and racism. That’s why my new talk, “Still Kicking: Confronting Ageism and Ableism in the Pandemic’s Wake,” tackles dual stigma and the potential for collective liberation. And that’s why I’m wishing for an intersectional 2021 and beyond. In the words of disability justice advocate Angel Love Miles, PhD, “Intersectionality demands that we work towards the liberation of everyone.”

Nowhere are the consequences of belonging to more than one marginalized group more tragically evident than in the havoc COVID–19 continues to wreak in long term care facilities—which, like the rest of our health care system, had already been largely privatized and set up to fail. More than 120,000 long term care workers and residents have died since the pandemic began. Less than 1 percent of America’s population lives in long term care facilities, but as of December 31, 2020, they accounted for 38 percent of US COVID-19 deaths. Residents are now dying at three times the rate they did in July.

Who lives in care homes? Older people and people with disabilities.

- Over 80 percent of Americans who’ve died of COVID–19 were aged 65 and over. Age does put us at higher risk—but not in these numbers.

- Unlike age, cognitive impairment is not a risk factor for COVID. Yet Americans with intellectual disabilities are far more likely to contract the virus than other people and at least twice as likely to die from it.

- People live in nursing homes not because they’re old but because they’re disabled. Ageism and ableism—seeing older and disabled people as less valuable members of society— legitimize their appalling abandonment.

Who works in care homes? Most care workers are women of color earning minimum wage or less.

- A society that doesn’t value its older and disabled members doesn’t value the people who care for us. This is especially the case if they are women, people of color, and/or undocumented immigrants. This describes most care–home aides, who perform a job more deadly than logging or deep-sea fishing—for poverty wages that require many to work more than one job in order to feed their families.

- Nursing homes with a significant number of black and Latinx residents have been twice as likely to be hit as homes whose populations are overwhelmingly white—no matter where they are, how big they are or how they’re rated. The risk factor isn’t race, it’s racism.

- What’s the good news? Activism is intersectional too. Just as different forms of oppression compound and reinforce each other, so do different forms of advocacy and education: when we confront any prejudice, we chip away at the fear and ignorance that underlie them all. A better world in which to grow old is also better place to be non-white, non-male, non-straight, non-rich—and vice versa.

There’s a regrettable human tendency to think about this in zero-sum terms: I can only manage one role! But that’s not how equity works. When we ignore or overlook what the most marginalized are up against, inequality increases, which harms people and reduces collective well-being. When we use our privilege to create circumstances that enable everyone to participate and contribute, on the other hand, we all benefit.

This path is messier and harder and longer. It’s also the sustainable, ethical and joyful path, and I’m glad to be on it.