How do you define successful aging? There are textbook definitions, but it’s a fair guess that we all know it when we see it.

The ability to age in place is one of the most common themes of successful aging. When I’m not writing for the Silver Century Foundation, I work as an independent-living consultant. I help people stay in their homes—even a downsized home—for as long as possible. My tasks run the gamut from bill paying to property management, from interfacing with health care providers to keeping pantries stocked. I help clients remain able to navigate their homes even if they do not drive. (Mobility is another piece of successful aging.)

My clients have sufficient wealth to maintain comfortable lifestyles. This relieves many of the challenges older people face and provides access to services that those with a low income may be denied. Yet what I’ve seen makes me wonder: financial security definitely enables people to age in place, but does it guarantee successful aging?

One client is a widow who lives in a large home with a big yard and a live-in caregiver. She developed depression after her husband’s death several years ago, so her sleep schedule is out of whack and she’s prone to falling from tiredness. She has a yoga instructor, fitness coach and massage therapist who come to the house. She enjoys their company but doesn’t care for the exercise. An accountant and financial advisor also come to her. She was once gregarious and outgoing, but her friends—who no longer know what a good time would be to call—have stopped calling, so outings are limited to adult children and grandchildren.

Another client is a brilliant woman whose husband has in-home hospice care. The couple always put careers first and never established a social network. They do not have family nearby. Their combined resources allow for unlimited support, including 24-hour caregivers, a housekeeper, a daytime caregiver/driver, a hospice nurse who comes on a schedule, a concierge doctor who visits and an omnipresent array of handymen. They have vacation properties they haven’t visited in years. I’m there to interface with the accountant and pay bills. My client goes out to physical therapy and to medical specialists. She feels her memory is too impaired to keep up with former professional colleagues, so she has no social life. Indeed, the staff, myself included, provide all of her conversation at this point.

Are these women aging well?

By way of contrast, I assist Tom,* who has an intellectual disability and shares an apartment with Mike,* who has autism. They live like messy adolescents. They spill, forget to clean up, clog drains, break things and leave windows open when the heat or A/C is on. But they abide by their budgets, shop and prepare their own meals, use public transportation and come and go as they please. They both have hobbies and enjoy going to local athletic events and holiday gatherings with family. Both Medicare-eligible, the men work low-skilled, minimum-wage jobs five days a week. Their work gives them social contacts and a reason to get up in the morning.

Who’s aging better?

I know other older adults whose astute financial planning affords them enviable opportunities in later life. I know women in their 70s and 80s who can take up bridge or go on long hikes if they’re so inclined. But when I consider how financial security impacts older people, it’s surprising to see that even with great privilege, aging well is not guaranteed. To age well, perhaps, is to remain relevant; it requires full participation and a level of emotional and physical health.

I want my own later life to have purpose, good company and a fully stocked bookshelf.

*Names have been changed to protect privacy

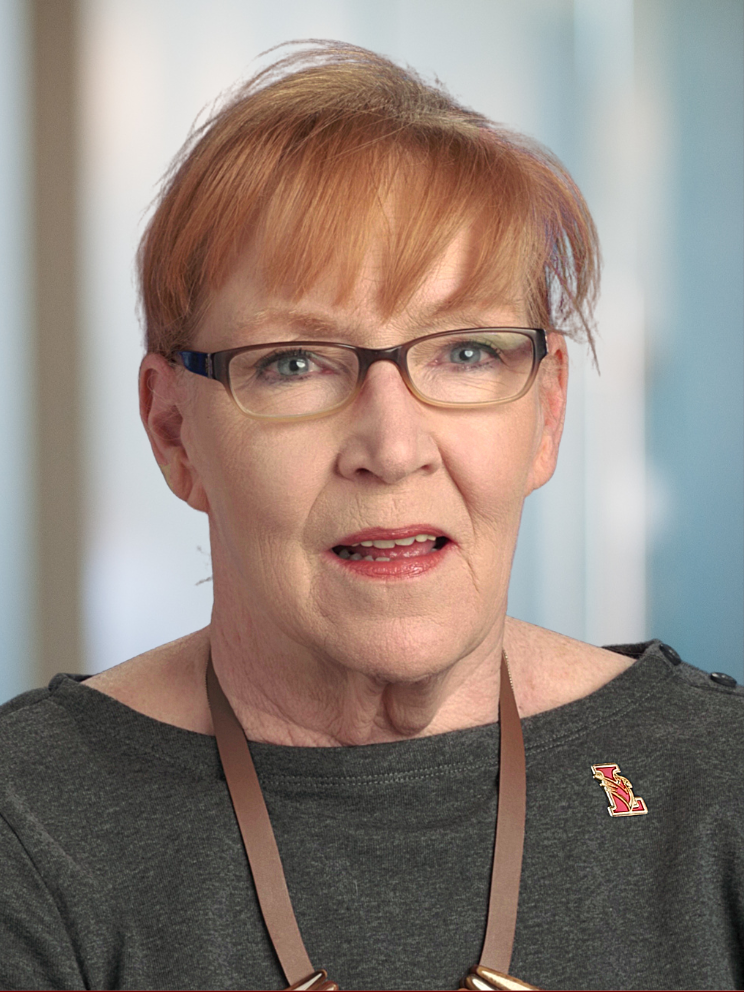

Pepper Evans works as an independent-living consultant, helping older adults age in place. She is the empty-nest mother of two adult daughters and has extensive personal and professional experience as a caregiver. She has worked as a researcher and editor for authors and filmmakers. She also puts her time and resources to use in the nonprofit sector and serves on the Board of Education in Lawrence Township, NJ.