2015, USA, 121 min.

The Intern is a Nancy Meyers movie, for sure—all sunny skies and characters with straight teeth living in Brooklyn brownstones straight from Architectural Digest. At first glance, it’s another one of Meyers’ puddle-deep salutes to woe among upwardly mobile seniors (It’s Complicated, Something’s Gotta Give). But the longer you stay with it, the more Meyers wins you over with her tale of two colleagues falling into a friendship. Of course, it helps to have Robert De Niro and Anne Hathaway obliterating the artifice.

De Niro plays Ben, a retired widower who has tried every conceivable way to occupy himself—from traveling to watching films to learning Mandarin. The days still feel empty. When he spots a flyer for a nearby company looking for senior interns, Ben jumps at the opportunity.

After a round of interviews with the far-younger folks in HR—one asks if he remembers his major—Ben gets a six-week slot working for the company’s founder, Jules Ostin (Hathaway), who is understandably consumed by her job. She tackles customer service calls, heads down to the shipping warehouse to show the staff how to pack orders. She is self-made all the way. “I’m not so fun to work for,” she tells Ben.

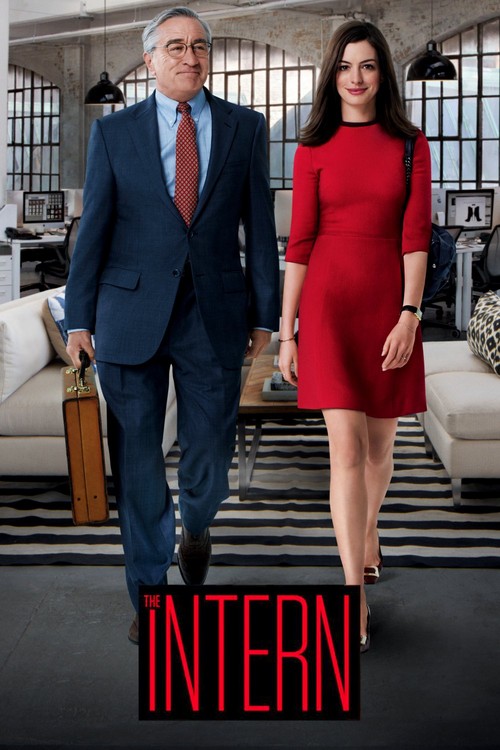

Jules bicycles through the office space and is usually tethered to a smartphone or laptop. Ben wears a suit and tie and carries a briefcase. But the two share industriousness and a pride in their work. She can’t ignore him forever, especially when he clears the office’s junk table—the bane of Jules’ existence—and jumps on opportunities, like becoming her chauffeur.

The arrangement causes a shift in dynamics, but it occurs in a very real way. Jules is skittish about Ben. After all, she built the company by herself. She has underlings, not associates, and here’s someone who is getting along with her husband (Anders Holm) and little girl (JoJo Kushner). Clearly, he wants something. Ben, however, has been through all this before—he was a sales and marketing executive for 40 years. He just wants to feel needed by someone. When he becomes the go-to guy for advice in the office, Ben says, “I feel like everybody’s uncle.” It’s not a complaint.

As Ben and Jules’ friendship deepens, we learn more about each character. Jules is sinking. As the breadwinner, she feels like she’s lost her footing on being a mom and a wife. The company is growing rapidly, and she’s being penalized both at work (the investors want to hire a CEO) and by the mothers at her daughter’s school, who treat her like she’s negligent. Ben’s struggle is Jules herself. Is he her assistant? Her mentor? Her confidante? (De Niro is so cool and self-assured here that you just know an evolving romance with a young woman who is his boss is repellent. Meyers gives Rene Russo a throwaway role as the office masseuse to douse any May-December notions.)

De Niro and Hathaway shed the personas that have stuck to them in recent years and bring the characters’ realness to the surface. It’s so refreshing to see De Niro not as a comedic foil but as a regular guy with a regular problem. Hathaway, who was the apotheosis of maudlin in that awful adaptation of the Les Miserables musical, is back to form here. She’s bubbly and charismatic, her character in The Devil Wears Prada 10 years later. Only this time the optimism has curdled.

Meyers doesn’t traffic in the obvious. There are no scenes of Ben struggling with an iPhone or Jules losing her child while trying to organize a conference call. The writer-director is more interested in examining what happens when we get to our dream destinations—in this case, retirement and leading a successful business—only to ask, “that’s it?” Because of her care in that area, it’s easy to overlook the movie’s flaws: its occasional veer toward slapstick (De Niro trying to hide an erection while getting a massage from Russo); the fact that this Brooklyn doesn’t appear to have a single minority. Also, Meyers still insists that her films be shot in the warm tones associated with commercials for fabric softener, an approach at odds with the seriousness of the material. In the end, Meyers gets one thing indisputably right: she treats her lead characters as adults.