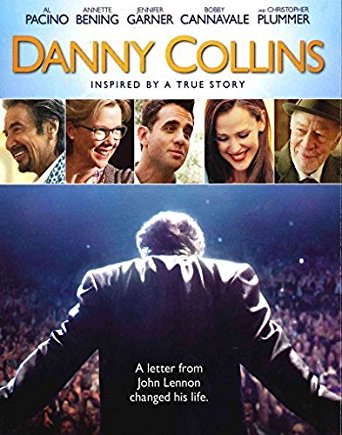

2015, USA, 106 min.

The winning, therapeutic Danny Collins teaches us something: namely, that the best things in a long life are usually the least glamorous. Al Pacino portrays the title character—an amalgam of Neil Diamond and Rod Stewart—who long ago abandoned creative integrity for pop-star prancing and all of its goodies—such as a much-younger fiancée, who doesn’t love him, and a mansion with an elevator. When Danny’s manager and best friend (Christopher Plummer, in another fine performance) gives him his birthday gift—a letter John Lennon wrote to a young, confused Danny—the star is struck. What if he had gotten that letter four decades ago?

The letter initiates a late-life crisis for Danny, who realizes that things matter beyond playing the hits to an aging crowd. (His disdain for the audience is Fogelman’s way of showing Danny’s shallowness. He can’t appreciate loyalty—even from the people who allow him his success.) He craves things that are real, or his version of them. So he boards a private jet for New Jersey, moves a Steinway into his room at the Hilton and sets out to write his own songs.

The Garden State provides more than the setting for an artistic rebirth. He wants to reconnect with the son he abandoned. Tom (Bobby Cannavale) is an honest-to-goodness adult with a lousy job, a family and a mortgage. The reunion goes poorly, much to Danny’s surprise. Elevated by his new-found bravery, he expected an instant happy ending. Tom, however, has little use for Danny, who breezes into his suburban abode dressed like he’s just finished a set at the Golden Nugget. Danny expects to waltz in, elevated by his seniority, success and bold gestures. His happy ending is far from guaranteed.

Danny’s attempts at reconciliation are guided more by money than kindness. He gets close to his daughter-in-law (Jennifer Garner) and granddaughter (Giselle Eisenberg), even getting the little tyke into a prestigious New York City school that can properly handle her ADHD. Afterward, he takes the kid on a shopping spree at Toys “R” Us. In a giant tour bus that features Danny’s car-salesman glare.

Director-writer Dan Fogelman doesn’t immediately give Danny the closure he craves. Neither do any of the characters. The lack of sugarcoating is refreshing. We like Tom for not making things easy for his father; this, in turn, connects us to Danny. Pacino is what draws us in. He brings so much warmth and depth to this peacock of a role. As the great actor has gotten older, the menacing confidence that defined his classic, 1970s work has given way to a confident skittishness. When he’s buttering up the hotel manager, played by Annette Bening—whose work here is so natural and understated she could be anybody’s friend—you also sense the desperation. Danny is in a whole new world, and he has to figure out how to make amends before the curtain falls.

We have all felt that desperation, and the sting when we can’t get it right. Deeply flawed and late to the game, Danny is finally learning how to be human. Danny Collins boasts surprising depth to go with its tenderness. Fogelman perfectly captures one of aging’s least understood truths: wisdom and clarity don’t automatically accumulate with each passing year. You still have to work for them—and, yes, it is totally worth it. If we are lucky, we can even get the chance to be our own kind of rock star.